John Weretka on a musical mystery in a painting by Master S.B. in the Museo del Prado Masterpieces exhibition at the NGV

Fig. 4 Master S.B. active, Rome 1633–1655 Kitchen still life (Natura morta di cucina) 1640s oil on canvas 78.0 x 151.0 cm Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid (P01990) Spanish Royal Collection Museo Nacional del Prado

Music features reasonably often in paintings and other art works and, as someone who works between musicology and art history, my eye is often drawn to these kinds of representations. Artists often take real care with the depiction of music. One of the most startling examples of this is the magnificently detailed Annunciation to the Shepherds (1587) by Jan Sadeler I (1550-1660) (fig. 1). Conforming to the normal tropes of the Annunciation type, it shows a choir of nine angels who hold the parts for Andreas Pevernage’s (1542-1591) motet on the text of the Gloria, in this way providing a kind of soundtrack to the image depicted. Similarly, Sadeler’s 1590 print (fig. 2) shows Solomon holding Pevernage’s Osculetur me in choir book formation. The work is based on Song of Solomon 1:1-2, reminding the viewer of the Solomon’s own ‘singing’ in the Canticum Canticorum and of the many great works of music that this book of the Bible has inspired.

Fig 2 (L) Annunciation to the Shepherds (1587) by Jan Sadeler I and Fig 3 (R) Jan Sadeler I, Solomon holding Pevernage’s Osculetur me, 1590

The National Gallery’s Italian Masterpieces from Spain’s Royal Court shows two works in which music features prominently. One of these, unsurprisingly, is the Amigoni group portrait (fig. 3) from the Gallery’s own collection that contains no fewer than two singers, soprano Teresa Castellini and the man who was probably the greatest castrato ever to have lived, Carlo Broschi detto Farinelli. Farinelli holds a sheet showing the music and words of the canzonetta La partenza. Farinelli’s initials feature boldly at the top of the sheet of music and this reminds us that Farinelli not only sang this music, but that he also wrote it. The fact that the author of its text and Farinelli’s close friend, Pietro Metastasio, sits at the right of the painting also makes it a kind of index of their relationship. The page of music Farinelli holds is thus unlike the brushes and palette that Amigoni, on the right, holds: it is not a sign of his métier, but of his great genius in two fields, singing and composition, and his link to and friendship with perhaps the most influential poet of the eighteenth century.

Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait group: The singer Farinelli and friends, (c. 1750-1752) oil on canvas 172.8 x 245.1 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1950 2226-4

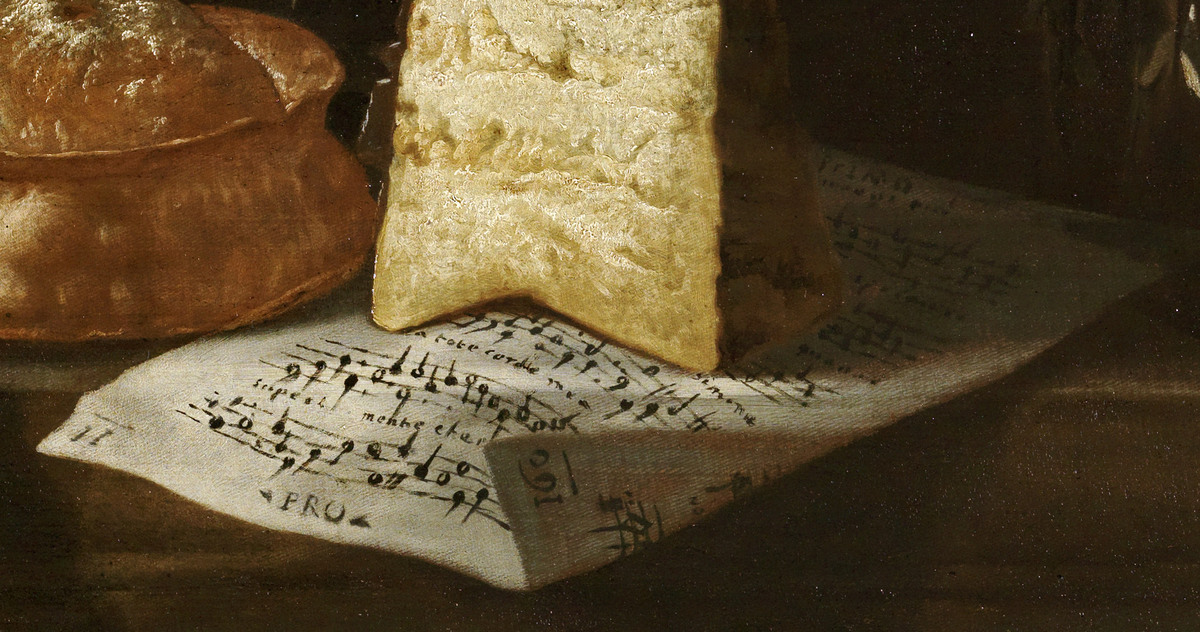

The other image in the Gallery’s exhibition featuring music is another kettle of fish entirely. This is Master S.B.’s Kitchen still life of the 1640s (fig. 4 above). The artistic personality of Master S.B. has come into focus through a series of recent attributions; he is assumed to have been a painter of still life active between Rome and Naples in the middle of the seventeenth century. Kitchen still life presents the variety of artfully arranged food items typical of the seventeenth-century still life with — somewhat unusually — what appears to be a fairly well drawn piece of music (fig. 5). But is this really a piece of music and, if it is, what does it tell us about the ‘meaning’ of the still life?

The recto of sheet of music is presented to the viewer, wedged partly under a block of cheese and partly obscured by darkness. It is evident that the sheet consists of six staves of musical notation, under all but the last of which is a text. At the foot of the page are what appear to be (left) a numeral, (middle) the letters PRO enclosed between two angled brackets and (right) another numeral, represented on the up-turned fold of paper.

Let’s start with the text. The text for the first three staves is almost completely illegible. Beneath the fourth staff, we read ‘…a toto corde meo’. The text below the fifth staff is also largely illegible. The text seems to begin ‘inpe…’; the second word seems to be ‘mente’ and the third seems to commence ‘eter…’. The language of the text seems to be Latin. ‘Toto corde meo’ means ‘my whole heart’; ‘mente’ is the ablative of mens (mind) and ‘eter…’ might be a declined form of eternitas (eternity).

If the language is Latin, the chances are — given the date of the painting — that the text is from the Vulgate Bible. The phrase ‘toto corde meo’ appears eleven times in the Vulgate Bible, ten of which are from the psalms and the last of which is from the book of Jeremiah. ‘Toto corde meo’, however, does not occur by itself, being prefixed mainly by ‘ex’ (out of) or, much more commonly, ‘in’, yielding ‘in toto corde meo’ (with my whole heart). All of the biblical uses of ‘toto corde meo’ are prefixed either by ‘ex’ or ‘in’, both prepositions more or less requiring the ablative, the case in which ‘toto corde meo’ appears. However, Master S.B.’s text seems to be prefixed by ‘…a’. Furthermore, none of the Biblical uses of ‘toto corde meo’ is followed within several verses by anything featuring mente. Is this a Vulgate text at all?

The phrase ‘[in/ex] toto corde meo’ is most significantly associated with the psalm Confitebor tibi (Ps. 110), settings of which were reasonably common in the Renaissance. These settings generally just set Ps. 110:1, Confitebor tibi Domine in toto corde meo (‘I shall confess you, O Lord, with my whole heart’), often as part of a centonised text, such as that used as the Offertory for Palm Sunday. Settings of it in this form were written by Palestrina and Lassus. Palestrina’s 1572 setting is for five polyphonic voices (CAT1T2B); Lassus’ 1585 setting is one for four voices (CATB), neither of which seems to bear any relationship to Master S.B.’s music. Assuming the intended text is from the Vulgate, however, it is likely to be from Ps. 110, as the other psalms in which ‘toto corde meo’ occurs (Ps. 9, 85, 118 and 137) have rarely, if ever, been set in the history of music. The remaining occurrence of ‘toto corde meo’, from the book of Jeremiah, is also from a rarely set text. We should note that Palestrina worked almost exclusively in Rome, as did Master S.B.

From a textual point of view, four hypotheses suggest themselves:

- The text is not from the Vulgate at all (unlikely)

- The text is a purpose-composed Latin text that happens to bear a relationship to a passage of the Vulgate (possible but unlikely)

- The text is not Latin at all (very unlikely)

- The text has been made to look as though it comes from the Vulgate (possibly with direct reference to Ps. 110) but is not actually a Vulgate text (highly probable)

That leaves the text at the bottom of the page. The marking to the left might be the numeral ‘11’ with a bar on top of it. Its meaning is unclear. The letters in the centre (PRO enclosed between angled brackets) are also of unclear signification. One sometimes sees words in this position in printed editions, referring to the name of a part book or printer but, as this is a handwritten manuscript, that comparison takes us no further. I believe that the up-turned corner at the right of the sheet does not reveal the rear of the music, but shows bleed-through from the recto. At first glance, this might appear to be the numeral ‘190’ with a bar on top of it, but if this is showing bleed-through, then the ‘9’ is around the wrong way. Again, its meaning is unclear. I would note that both ‘numerals’ have bars on top of them.

That leaves us with the music itself. The good news is that note-shapes are all basically correct and were current in the mid-seventeenth century. We can recognise semibreves, minims and crotchets with ease, and rests even appear to be drawn in. The absence of bar lines is also consonant with the presumed date of the music. These features — particularly the note shapes — give us enough information to register that this is a piece of music, perhaps even a real one.

Closer inspection starts to break this impression down, however. The music is written on a four-line staff. The number of lines in the staff has actually changed considerably over the history of music, but the four-lined staff has really only ever been used consistently for the notation of liturgical chant (which this music clearly is not); the five-lined staff has been the dominant type since the thirteenth century for most general uses.

Notwithstanding the number of lines in the staff, the presence of a text should help us to work out what kind of work is intended. This is clearly not a vocal composition in the ordinary sense of the term, as most vocal compositions in manuscript form were transmitted in single-melody line and text sheets. The music in Master S.B.’s painting could not be sung by a single person and, indeed, the presence of a Latin, possibly Vulgate, text points us in the direction of the dominant Latin-texted composition, the polyphonic motet. Accordingly, this could be (1) either a vocal composition for several voices that has been compressed into single-staff notation, possibly for some kind of performance at an instrument or (2) some kind of composition for an individual voice with some kind of instrumental accompaniment presented on one staff. Examples of the latter are known, including in Miguel de Fuenllana’s Orphénica lyra (1554) (Fig. 6), in which the vocal part is notated in red to an intabulated vihuela accompaniment in black. This work is part of what was originally a four-voiced polyphonic motet, Hodierna lux, by Lupus (fl. 1518-1530).

If some kind of instrumental performance were expected, which instrument was expected to be used? The instrument would clearly have to be one capable of playing polyphonic music. In the period in which Master S.B. was active, these would be keyboards, plucked strings, and certain bowed strings (e.g. the viola da gamba). Plucked strings and bowed strings that aspired to play polyphonic music would play in tablature, generally notated on a staff with a number of lines equivalent to the number of available strings (never as few as four) and generally in either alphabetic or numeric notation (not Master S.B.’s normal musical notation). Keyboard players often played reductions of vocal polyphonic music, but they did this either from tablature; or from a set of complete vocal part books or a choir book, playing all parts simultaneously (as the angel at the organ is doing in Jan Sadeler’s print) (Fig. 7); or from printed keyboard notation on a grand staff very similar to today’s keyboard notation. None of these situations matches what we see in Master S.B.’s notation.

Finally, although the note shapes are right, much else is wrong. A clef, which would tell us the absolute pitch of each note and has been deemed a must-have feature of music since the late ninth century, seems to be completely omitted in Master S.B.’s music. There is no indication that the music has been coordinated according to a time signature, there is no sign of regular rhythmic organisation, nor any of the vertical organisation of voices that all but the most wayward and hastily-drawn of music sources shows in polyphonic music. Finally, the semibreve in the middle of the last staff shows what appears to be a sharp placed after the note. While post-placement of sharps is not unknown in earlier music, then as now the most usual placement for a sharp was before the note it affects.

In sum: the literary text of Master S.B.’s music is a fake and so, despite some serious attempt to the contrary, is the musical notation. And to think we were suckered for a moment…

Music appears in four other paintings by Master S.B., perhaps the same sheet. It would be interesting to have access to images of these other sheets. If anyone can help, please let me know.

© John Weretka 2014

I am an artist. I paint to music. And some years ago, I designed a stained glass window for a violinist.

I used musical notation, but did not worry about musical conventions.

When I paint flowers, I paint the sense of a flower; when I paint seascapes, I paint the sense of the sea.

And when I made my window, I put together coloured pieces of glass to convey a sense of musicality.

I suppose that to a botanist, my flowers would not merit much? And perhaps to a musicologist, my musical pictures would provoke disdain?

And yet, at the end of the day, through a distillation of the essence of each one, I convey their beauty and their essence, going beyond the specific to the real spirit of things.