Exposing Thomas Clark: a colonial artist in Western Victoria

David Hansen

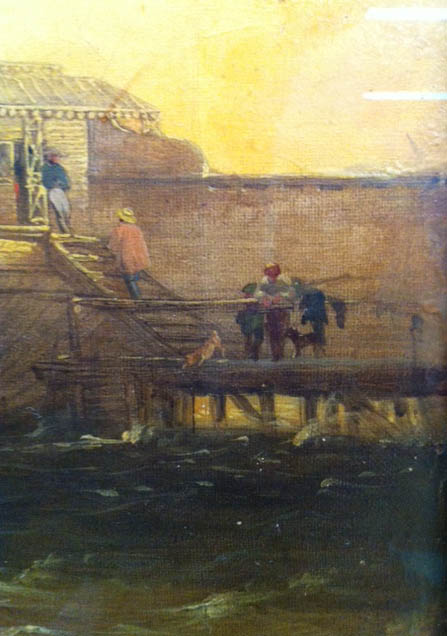

Fig. 6 Thomas Clark, 'The Wannon Falls (Proscenium View)', c.1860, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection. Via exhibition website

The exhibition runs at Hamilton Art Gallery 21 September – 17 November 2020

At a small but intensely stimulating symposium hosted by the University of Melbourne in November last year, a variety of curators, scholars and writers met to share experiences, insights and ambitions relating to exhibitions of Australian colonial art. Coffee breaks and plenary sessions were particularly interesting in articulating outstanding desiderata for monographic shows: Mary Morton Allport, Thomas Baines, Ludwig Becker, Louis Buvelot, J. H. Carse, Augustus Earle, S. T. Gill, Thomas Wainewright … . Nobody mentioned Thomas Clark, because everyone at the conference knew that Danny McOwan was already working on that one. Had been for quite some time, in fact. Well, that long-anticipated exhibition has finally made it onto the newly and smartly plastered, sky-blue painted walls of the Hamilton Gallery. And it is a revelation. As painstakingly excavated by researcher and curator Dr Peter Dowling, Clark’s oeuvre totals thirty-five located and certainly attributed oil paintings; a full thirty-one of them are in Exposing Thomas Clark, allowing the full range of his achievement (in this medium, at least) to be explored.

Fig 1 Ulysses and Diomedes Capturing the Horses of Rhesus, King of Thrace, 1851?, oil on canvas, 109.3×193.6cm, Bendigo Art Gallery.

The quality is there from the very beginning, in the only pre-Australian painting known to have survived, the self-advertisement picture that Clark brought with him to Victoria when he emigrated from Nottingham in 1856: Ulysses and Diomed capturing the horses of Rhesus, King of Thrace (Fig. 1). This academic ‘machine’ has graced the walls of the Bendigo Art Gallery since 1904. Although it was recently described by John McDonald as a ‘woeful slab of … schmaltz’, here in Hamilton, up close and personal, it appears rather as a very interesting survivor of the neo-classical turn in British painting, as exemplified by Benjamin West, Thomas Stothard and Benjamin Robert Haydon, or perhaps an equally interesting precursor of the more scholarly-archaeological Grecianism of Edward Poynter and Albert Moore later in the century. But beyond its art-historical details—from the remarkable palmette-moulded frame to the Parthenonic horses’ heads to the foreshortened fallen warrior in the foreground (from which Italian mannerist has this figure been borrowed?)—the picture has a very distinct personal character.

The eight equine forelegs at the front of the action not only recall that stop-motion rotation device that Jacques-Louis David uses in The Oath of the Horatii, but at the same time have a rather disturbing, almost surreal crab-like character. A similar weirdness is seen in Ulysses’ saddlery, in the leopard skin which appears to be flying along between a couple of horses of its own volition, like some ghastly dream apparition, a feral flying carpet. Finally, Ulysses wears—evidently as the result of a mistranslation from Homer—not a ‘boar’s tusk helmet’, but one made of an entire boar’s head, with the animal’s tusks and teeth forming an ivory diadem.

Fig. 2 Thomas Clark, 'Melbourne from the Botanical Reserve', 1854, oil on board ; 29.2 x 45.0 cm. (sight), in frame 45.8 x 62.0 x 3.0 cm. This work is out of copyright

Just the same sorts of eccentric surprises are to be found in the corpus of Australian landscape paintings. We have become accustomed to thinking of Clark—if indeed we do at all—in terms of environmental and social history. We tend to see his pictures merely as illustrations of such things as the state of the grasslands of Australia Felix a generation after the cessation of regular Aboriginal burning and the introduction of hard-footed European animals; the original appearance of the Red Bluff at Point Ormond on Port Phillip Bay before its demolition to provide landfill for the Elwood swamp; the St Kilda sea baths that Capt. William Kenney contrived out of the hull of an old whaling brig in the mid–1850s; even the Mahogany Ship, a semi-mythical shipwrecked Portuguese caravelle on the beach near Warrnambool (though here it is pretty convincingly argued that Clark’s views of a broken vessel are more likely to depict Stephen Henty’s schooner Sally Ann).

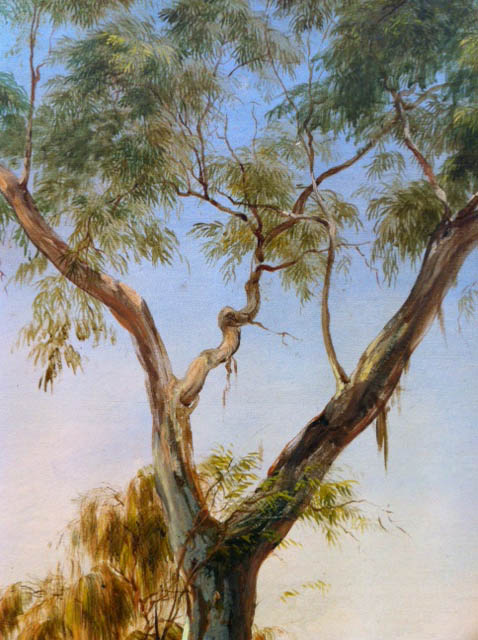

Fig. 3 Thomas Clark, A view of Mr Winters Run, c.1860, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection. Via exhibition website

What Exposing Thomas Clark does indeed expose is that before or beyond such incidental visual factoids, such informational value, Clark is quite simply a terrific painter, an artist who brought to Victoria a decade before Buvelot the late Georgian British version of plein-air sketching, the ‘natural painture’ of John Constable, Richard Parkes Bonington and the Norwich School. It comes as no surprise to be informed here that it was Constable who sponsored Clark’s application to the Royal Academy Schools, and we remember that at the other end of the century of naturalism both Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin were amongst his pupils in the 1870s. Clark’s paint application is broad, confident, fast, on occasion—as, for example, in Melbourne from the Botanical Reserve (Fig. 2)—even dashing. His colour is bright, often translucent. He paints the Western District’s grassy sward in great swathes of green, something like the hills of George Catlin—celebrated painter of Native North American land and lifeways—but without the buffalo. The arboreal native vegetation of the region is sensitively represented, too. Peter Dowling claims that the river red gum in the foreground of Mr Winter’s Run [DM4] on the Wannon (Fig. 3) is ‘arguably the most perfectly painted eucalypt up to this time’, and both here and in other paintings, gum trees, acacias and casuarinas are carefully observed and precisely and economically rendered. Clark’s rocks are painted in such thin glazes of earth colours (umber and sienna, both raw and burnt) that you can often see the pencil underdrawing marking the lithic cracks and edges, while his roseate gloaming skies and clouds have a naturalism and a delicacy passing rare in colonial painting. He is so much lighter (and more consistent) than his contemporary Nicholas Chevalier, and if he does not have Eugene von Guérard’s precision draughtsmanship, he more than makes up for it in the generosity and fluency of his brushwork.

Fig 3a. Detail of Thomas Clark, A view of Mr Winters Run, c.1860, Oil on Canvas, Private Collection. Via exhibition website

However, for this viewer at least, the most striking discovery of all is the richness of his staffage. In almost all of Clark’s landscapes, whether domestic pastoral station portraits or the geological sublime of waterfalls, caves and coasts, there is an abundance of figures, both human and animal. Sometimes it is just a conventional displaced and government-blanketed Aboriginal or two in the near foreground. But often there are more, frequently shown in telling and highly naturalistic attitudes, and just as often of miniscule dimensions: five millimetres high or even less. In fact, they rather resemble the little bobble-bodies found in Canaletto’s and Guardi’s views of Venice.

Fig. 4 Thomas Clark, 'Coast scene, St Kilda', 1857, oil on canvas, 48.4 x 94.4 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1969, Not on display

The bullocky in Coast Scene, St Kilda (Fig. 4) is shown lighting his pipe as he walks along; in Kenney’s Baths (Fig. 5) next to a man and a boy leaning on a rail over which bathers have laid their coats, a little dog barks excitedly at the waves below; in Wannon Falls (Procenium version 1) (Fig. 6 above) a man and his horse can just be descried on top of the rocks on the right, while along a ridge in View of Muntham Station (Fig. 7 above) ‘unassisted through each toilsome day / with smiling brow the ploughman cleaves his way.’ In Muntham Station we get a full domestic narrative: not only are there the compositionally obligatory near-foreground figures—a stockman with a horse and foal—but behind him we see a couple and a child walking up the garden path from their carriage, towards another family group awaiting them at the homestead. The host leans against a verandah post, hands in pockets, the very image of relaxed proprietorship, all in seven or eight deft touches of a fine brush. Off to one side, two even tinier red spots make a whole horse looking over the fence. In fact, as for people, so for animals: in View of Den Hills near Coleraine (Fig. 8) you could count the abundant cattle one at a time, while tucked away in the shadows and interstices of the land, indigenous fauna—wallabies, emus, brolgas, magpies, ducks—just keep on keeping on.

A bit like regional galleries really. As a former provincial director myself, and a continuing, enthusiastic advocate of cultural decentralisation, I certainly would not wish to deny the agency or, beyond that, the serious curatorial ambitions of regional institutions. The older galleries such as Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong, Newcastle, Wollongong and New England, have always punched above their weight, both in collections development and in exhibitions and publications. The 2011 Nicholas Chevalier: Australian Odyssey staged by the Gippsland Regional Gallery was a pretty creditable endeavour, especially given the rapidity with which it was assembled. Soon, we shall see Geelong’s take on Louis Buvelot, the first survey of the artist’s work in half a century. I must however register a certain disappointment that colonial artists of this calibre and historical importance have been so neglected in recent years by the larger, more central and consequently wider-reaching and better-resourced city institutions: the National Gallery of Australia (though they did at least give us Robert Dowling in 2010), the six State galleries and the various metropolitan university art museums.

Struggling personfully to pick up the slack, the regionals do not always have the curatorial breadth or focus of their city counterparts, or easy access to professional networks and conversations, and because regional gallery directors are prone to encouraging their work experience program curatorial staff and to supporting the local economy through engaging local wedding photographers and butcher’s calendar printers, and because there is never, ever enough money for consultant editors and designers, specialist essayists and the like, their catalogues of major shows can be somewhat untidy, inconsistent, ill-bound affairs. As, sadly, is the case here, despite the curator having so conscientiously done the hard yards of archival research.

Fig. 8 Thomas Clark 'View of Den Hills near Coleraine', c. 1860 Oil on Canvas Glenelg Shire Council Cultural Collection, Portland

Still, the essence of curatorial achievement—whether aesthetic or academic—ultimately lies in the experience of the works themselves, in the direct encounter with objects and their makers. So unless these shows travel (and given the considerable costs in dollars, time and labour, the available grants and cost-share returns are rarely sufficient to make touring economically worthwhile), it can be necessary for the art-interested to drive a long way for an uncertain outcome. It was relatively easy with the frocks at Bendigo and the flowers at Ballarat, both institutions being accessible by train. Hamilton? Four hours drive from Melbourne. (Though if you time it right, there is a nice lunch stop at Dunkeld’s Royal Mail Hotel.) So let me say it now: go. It is worth it. And take it from a veteran brown art guy: you won’t see this much Thomas Clark again for another 50 years.

© David Hansen 2013

1 comment for “Exhibition Review | ‘Exposing Thomas Clark: a colonial artist in Western Victoria’. Reviewed by David Hansen.”