Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart

Anna Drummond

‘So here are my thoughts laid bare for all to ignore.’ David Walsh

The Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania’s much-hyped art museum of sex and death, has just turned two. Built to house the personal collection of gambling millionaire David Walsh, MONA was opened to much fanfare and speculation in 2011. Two years on, has the gallery grown into a contrary toddler peddling the smutty and macabre, or a robust and confident youth cementing its place in the Australian cultural landscape?

MONA is certainly confrontational and undoubtedly provocative. With its focus on sex and death undiluted, the museum’s desire to shock is unchanged. Yet despite its professed themes, the collection on display is neither smutty nor macabre. The sex-themed gallery for example is thoughtful rather than titillating, despite playful nods to the erotic such as the long wall of red velvet curtains. Here the art is mostly about ideas rather than provocation: the looming genitalia that dominate Jenny Saville’s portrait Matrix, for example, belong to a bearded transsexual whose image raises a series of questions about femininity, body image and gender. Whilst not all the work is serious—particularly the substantial corpus of works by YBAs—this is art about ideas rather than titillation. Nor are the galleries that are loosely devoted to death particularly macabre, although the regular breaks from the dark exhibition space are helpful. There is, however, the occasional exception: Jenny Holzer’s Lustmord made my skin crawl and wedged itself solidly into my head for some time afterwards. Lustmord is a collection of statements about experiences of wartime rape taken from victims, perpetrators and witnesses who were often family members. This and Meghan Boody’s modified pinball machine entitled Deluxe Suicide Service as well as the same artist’s tutu-wearing pre-pubescent female dummy in a rabbit cage (The Mice and Me) create an unsettling few minutes of viewing. But, in general, the experience is not terribly dark and it is punctuated by humour. Erwin Wurm’s Fat Car, for example, is a full-sized Porsche puffed into obesity by some creative panel work and stands as a comment on western consumption.

Mixed in with the permanent collection of contemporary art is the hoard of antiquities that kick-started Walsh’s collecting. Rather than being relegated to a dry gallery of pots and trinkets, these are successfully incorporated into the galleries on sex and death. There are occasional unexpected juxtapositions but mostly they fit well with the various themes, mummies in the upper level galleries that explore mortality, for example. Another mummy is displayed in the body-and-sex-themed gallery alongside Stephen J Shanabrook’s cast of a disembowelled suicide bomber rendered in chocolate (On the Road to Heaven The Highway to Hell) where it prompts a contemplation of organ removal and the mummification process. In the same gallery there are a variety of small antiquities visible only through peepholes, a playful presentation that suggests they are forbidden. This is perhaps appropriate given the ethical questions regarding provenance and looting that are raised by any private holding of antiquities.

As a study of contemporary collecting, Walsh and his hoard seem ripe for the picking, but the curious visitor is given very little background. Why the gambler’s collection focuses on sex and death is not really explored; neither in the collection texts nor in the Walsh’s personal introduction to the museum catalogue. The radical change in his collecting interests—from antiquities to disemboweled suicide-bombers rendered in chocolate—is a transition that suggests a personal journey of discovery. The texts in the ‘O’ tour and references to personally commissioned works suggest someone deeply involved in the formation of his collection. They also demonstrate his dry sense of humour; commenting on a commission to artist Brigita Ozolins, Walsh notes, “I wasn’t very concerned about it being crap for two reasons. Brigita makes good stuff and also I could easily have plastered up the door [to the installation] and no-one would have been the wiser. This turned out not to be necessary.”

Walsh even extends his collecting to his visitors, who can be absorbed bodily into the collection for perpetuity if their funds allow. A mere $75,000 buys the particularly enthusiastic visitor an eternity membership, which—appropriately for this collection—continues after death. Post mortem, the ashes of eternity members are incorporated into the collection and displayed alongside Julia DeVille’s Cinerarium, an urn-like egg that purports to contain human ashes and bears a plaque recording the dates of life and death of a member of the Walsh family. Whether this is MONA’s first ‘eternity member’ is unclear.

The current temporary exhibition Theatre of the World is less successful. As eventually becomes clear to the visitor (but would have been more helpfully announced upfront), this is a selection of objects from the collection of the Museum of Tasmania. It is curated by Jean-Hubert Martin and arranged thematically. There is interest in some of the pieces selected. For no particular reason other than its incongruity I loved Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled, a wooden chair bearing an enamel bowl in which two goldfish swam puzzled around a large kitchen knife. Yet the linkages often seem contrived and the whole experience is somewhat disjointed. Or perhaps it just seemed rather conventional compared to the permanent collection of MONA.

While gaining permanent entry to the collection is somewhat expensive, understanding and enjoying MONA’s collection is much easier. In fact I suspect that a key part of MONA’s success is its accessibility. Entry is free for Tasmanians and the institution seems dedicated to appealing to a broad audience and eschewing an elitist or high-culture identity. This is evident in the casual language and provocative slogans of its marketing and communications: ‘Please buy something from our shop. There is all sorts of shit in here’ or ‘There’s a map showing you how to avoid some of the confronting stuff. Keep the kiddies clear’ and the museum catalogue is cheekily entitled ‘Monanism’. Even the onsite brewery produces beer ‘suitable for bogans’. Yet the slick execution of the building and its operation keeps the conventional middle-class gallery audience on side; everything down to the fireguard in the foyer is designed to match the prevailing aesthetic and or display the museum’s logo.

This quest to connect to all comers is perhaps best exhibited by the ‘O’ an iPod touch that replaces wall labels. The iPod finds works in the vicinity and then provides the viewer with as much or as little information as they choose; the works and information accessed can then be saved to the gallery website for later perusal. The ‘O’ includes everything from the basic details of the work to themed songs, sound bites from the artist, reflections from David Walsh and even provocative comments by others, some of whom ardently dislike the works. There are no reflections on the artist’s technique or redundant comments on perfectly evident brushstrokes. Instead the guide goes all out to be accessible and poke fun at conventional museum approaches; the brief curatorial summary for each work is listed as ‘Art Wank’, accompanied by a phallic icon. The ‘O’ also allows the viewer to click that they ‘like’ a work of art, Facebook-style, or alternately ‘hate’ it: a nod to twenty-first century interactivity. The ‘O’ strikes a successful balance between the postmodern museological convention that the visitor should not have the meaning of the work dictated by the institution, and enhancing the viewer’s appreciation of the work by helping them understand it. Requiring the viewer to actively seek information might prompt them to take in the art itself before being influenced by text. But, often during my visit more heads were still bowed over the device than levelled at the works, but it’s a start.

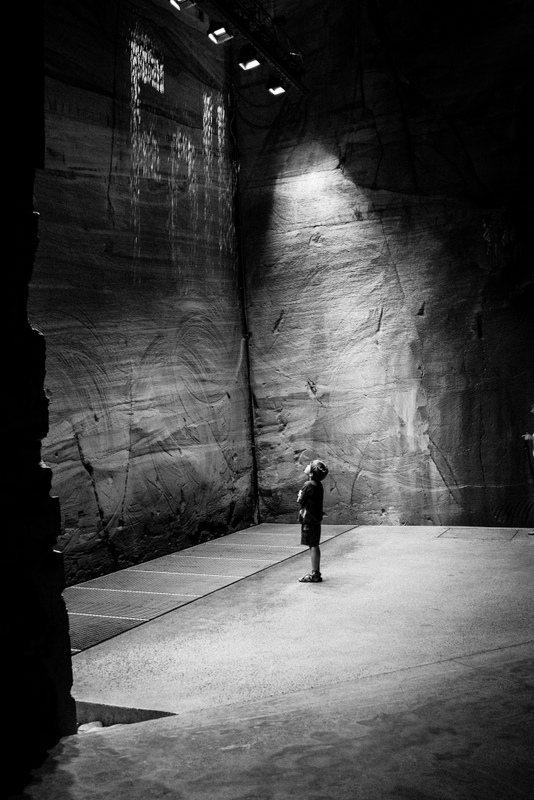

The architecture of the museum also rejects conventions; white walls are largely eschewed in favour of plain sandstone. The museum’s three levels of exhibition space underground, excavated out of Tasmanian sandstone are well suited to the collection’s focus on death. By contrast, above the galleries are the café and entrance created from a pre-existing house by Roy Grounds that is as airy and peaceful as the galleries are dark and intense. The exhibition spaces are alternately intimate and cavernous, and at times clearly purpose-built for particular works, such as the multi-storey space carved out for Julius Popp’s Bit.Fall, which spits sheets of droplets that form metre-high falling words that have been trawled from the internet.

Any kinks in the operation of the museum seem to have been ironed out. Staff are young, enthusiastic and well trained; the entry process characteristically unconventional but undeniably efficient. Even transport to MONA, like most things about the museum, is a well-thought out piece of theatre: a pristine ferry runs from central Hobart, offering coffee and a licensed bar on board. The only poorly thought-out part of the experience was the foyer toilets: a total of three, unisex. It is as though Walsh planned a grand temple to his own folly whilst maintaining a secret doubt that anyone would visit, that his thoughts would be ‘laid bare for all to ignore.’ Any such doubts have proved unfounded. Enjoy, they might well, criticise, quite possibly, but ignore–never. Sometimes challenging, always thoughtful, it is a monument to one man’s taste that has so far appealed to thousands.

© Anna Drummond 2013

MONA website http://www.mona.net.au/

The Theatre of the World exhibition runs until April 8th 2013.