James McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in grey and black no. 1 (Portrait of the artist’s mother) 1871, oil on canvas, 144.3 x 162.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RF 699)

The National Gallery of Victoria’s latest loan exhibition is based around a single painting by James McNeil Whistler – his Arrangement in grey and black no. 1 of 1871, popularly known as the Portrait of the artist’s mother, or just ‘Whistler’s Mother’. Compared to the just-closed Warhol/Wei Wei summer blockbuster, this is a small, intimate exhibition. The painting is on loan from the Musée d’Orsay and the exhibition is filled out with etchings, prints, paintings, furniture and decorative arts from the NGV’s permanent collection. The exhibition sets this single painting into a fresh context, one that enriches our understanding of Whistler and allows us to see works from the NGV collection in a new light.

Installation view of Whistler’s Mother at NGV International, 25 March – 19 June 2016.

Photo: Brooke Holm

I find it impossible to really talk about this exhibition without first dealing with the language being used to promote it. We are told (in the marketing and in the exhibition) that the painting is ‘iconic’ (a word that makes most art historians flinch just a little). It is a masterpiece that sits ‘alongside da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Munch’s The Scream’ it enjoys ‘universal recognition and admiration’. That the painting is famous is true, though, as with so many ‘iconic’ paintings, it has been made world-famous not really through universal appreciation of it as a work of art, but more through universal recognition. After being given a lukewarm reception when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1872, it’s worth was recognised when it became the first painting by an American artist to be purchased by a French museum. When the painting toured the United States in 1933 it drew the admiration of the American public and Franklin D. Roosevelt, not for its formal qualities as painting but for what they saw as a portrayal of stoic motherhood. Roosevelt designed a postage stamp (below) featuring the painting but with the mother isolated from the rest of the composition and given some flowers. More recently it has featured in television shows like The Simpsons and in the Mr Bean movie. None of this is to suggest that the painting is artistically valueless, quite the opposite, but more to introduce the idea that we often use iconic when we mean familiar and well-known, like a famous brand logo. ‘Iconic’ paintings are known by millions who have never seen the original; we have usually only seen reproductions, or adaptions. This is certainly true of Whistler’s Arrangement. I’m still not sure that the Whistler fits Martin Kemp’s good definition of a visual icon from his Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon, which proposes that an iconic image is ‘one that has achieved wholly exceptional levels of widespread recognisability and has come to carry a rich series of varied associations for very large numbers of people across time and cultures.’

United States postage stamp,1934

Does Whistler’s Mother fit the bill? Perhaps, and perhaps exhibitions like this serve to push it further along that path. The journey of an image to icon status is always a fascinating one, and it’s a shame this wasn’t pushed harder in the exhibition in a critical way. For the most part the exhibition falls back on a narrative that suggests that the painting has become iconic because it is a masterpiece, as though from the moment Whistler had finished there could be no other trajectory for it. But, as iconic images go this Whistler is a ‘quiet’ painting, I found it took time and consideration in front of the painting to begin to appreciate what Whistler was trying to convey.

Installation view of Whistler’s Mother at NGV International, 25 March – 19 June 2016.

Photo: Brooke Holm

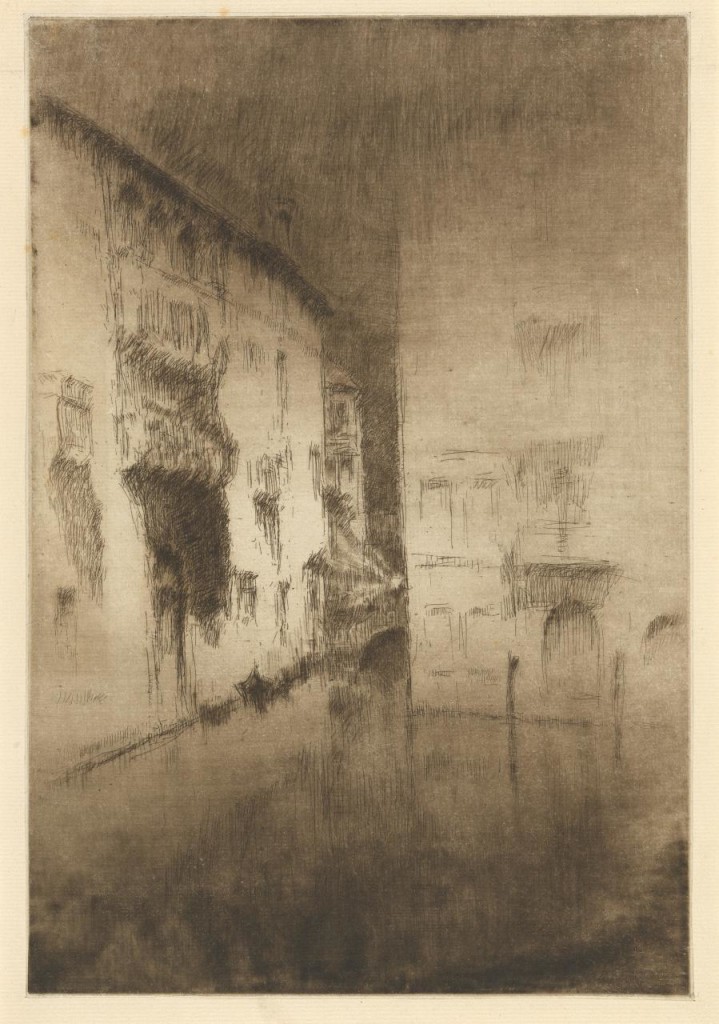

The exhibition is laid out across several rooms on Level 2 that usually display the Dutch and Flemish works from the permanent collection. On entering the space Whistler the man and the artist is introduced via a series of gauzy, see-through reproduced portraits of him and details of his works. Next we see a reproduction of the famous ‘Whistler’s Mother’ postage stamp and then turning the corner we finally get to see some art. Arranged along the right-hand wall are etchings from Whistler’s series of streetscapes, views of street life, and portraits from Paris, Venice and London. The exhibition text suggests that these etchings provide context by showing us the places where Whistler worked, which they do, but for me the more interesting thing is that they show his technique. In the monochrome etchings we can see Whistler’s keen sense of how to contrast light and dark, sharp lines and hazy edges, and how to find a balance between fine detail and more abstract suggestion. In his Nocturne, for instance, he conveys the sense of ghostly Venetian palaces emerging from a dark foggy night with short thin vertical lines (which recall the Japanese prints that Whistler collected). The short dashes are sparse where they suggest the facade of the palazzo and thick where the shadows gather as the canal disappears between the buildings; the water seems more substantial than the palaces.

James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Palaces, (1880-1886); printed 1886, plate from A set of twenty-six etchings (or The second Venice set), 1886

Diagonally opposite the series of etchings is a group of Australian paintings including works by Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, Bernard Hall and John Longstaff. This shows the connection between Australian art, Whistler the artist, and ‘Whistler’s Mother’. At this time it was common, if not expected, that young Australian artists would decamp to Europe and set up studios or attend classes in places like Paris and London. The connection is a substantial one, Longstaff was in Paris when the Musee d’Orsay acquired ‘Whistler’s Mother’ and probably went to see it when it was on display.

View of paintings by Australian artists John Longstaff, Arthur Streeton Bernard Hall, Charles Conder, and others. Installation view of Whistler’s Mother at NGV International, 25 March – 19 June 2016.

In the next room we find a range of decorative arts – a Japanese screen, ceramics, and woodcuts. On one wall are Japanese woodcuts by Hiroshige and Gakutei, of the type that Whistler collected. More etchings by Whistler hang alongside, and comparisons and contrasts can be made between the compositions of each. In the centre of the room is a sideboard designed in 1867 by E. W. Goodwin, demonstrating the European fascination with Japanese decorative art., from the black finished meant to imitate Japanese lacquer to the balance between void and solid shapes in the overall composition. Not only do these prints ‘stand in’ for those Whistler owned, but they also reflect that at the time when Whistler and other artists in Europe and America were collecting Japanese art, so too was the NGV. Bernard Hall (whose painting ‘The Connoisseur’ (above) hangs in the previous room) was director of the NGV for over 40 years and he was instrumental in the formation of the NGV’s collection of Asian art. The Japanese woodcuts in this room were both purchased while he was director, as were several of the Whistler etchings.

Japanese woodcuts by Hiroshige and Gakutei.

Installation view of Whistler’s Mother at NGV International, 25 March – 19 June 2016.

Although the sentimental side of the portrait of ‘mother’ is pushed a little too hard in the exhibition, once you stand in front of the painting for a few minutes you begin to see that Whistler’s original title Arrangement in grey and black no. 1 is more fitting. I was struck by the idea that the figure of mother is both central and secondary. On the one hand it is a portrait (the wall text reminds us that people who knew her recognised her) but there is also a sense that Whistler’s mother is merely the subject for a painting of a ‘domestic interior with an old woman’. In this sense there is a link with the Longstaff painting of the mother and baby in the first room, it too is not so much a portrait of a specific woman, but a study of a woman and a child; a deliberation on whites, greys and blues and a glimpse of a moment of intimacy between a mother and her child. In both the Whistler and the Longstaff painting I do not really get a strong sense of their personalities as individuals.

John Longstaff, The young mother, 1891, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 169.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds donated by the NGV Women’s Association, Alan and Mavourneen Cowen, Paula Fox and donors to the John Longstaff Appeal, 2013, (2013.766)

To return to the Whistler , it is the possibility for exploring texture, shade, composition and colour that I found really absorbing. I found my eyes drawn first to her face, but as it is in profile there is nothing much to draw us in to a study of ‘her’ so instead the eye follows her silhouette from the white bonnet down across the profile of her face to her lap where the lace-cuffed hand holding a handkerchief briefly interrupts the sea of black. From here the eye follows the line of her legs down to her feet and from there we can step back a little and note the contrast between the figure of the mother and the geometrical arrangement of the rest of the composition. To the left the curtain hangs in folds but presents as a patterned rectangle, rather than a sweep of drapery, and indeed, the rest of the composition is essentially a series of rectangles in different shades – the light grey wall, the framed etchings, the brown box she rests her feet upon. Up close you can see how Whistler uses the weave of the canvas to add texture and shade, dragging his brush across it so that raised weft and warp catch small dabs of paint. This is particularly apparent in the way he has created the look of the lace edging on the bonnet, on the cuffs and the handkerchief. There are also similarities in texture and shading to the Whistler etchings to be drawn out as well, for instance, the black skirt of Whistler’s Mother’s dress falls down toward the floor, where the blackness of the skirt merges with the brown floor in a series of feathery brush strokes, recalling the shadows in the Nocturne mentioned above.

Installation view of Whistler’s Mother at NGV International, 25 March – 19 June 2016.

Photo: Brooke Holm

This a small but well-formed exhibition, my only general criticism is that the space feels slightly too large. On the one hand devoting an entire room to ‘Whistler’s Mother’ allows space to really focus in on a single work, but on the other it also divorces the key painting in the exhibition from the rest of the works that meant to provide the context. This is the type of exhibition that encourages visitors to pop in to the gallery for just an hour or so and to spend some time looking at a small selection of works in detail, the type of visit I think should be encouraged as it provides a pleasant counterpoint to the (also enjoyable) experience of devouring a large blockbuster exhibition.

The exhibition runs until June 19th 2016. See the website for further information: http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/whistlers-mother/

© Katrina Grant May 2016