MAN looks at Men: Masculin/Masculin: L’homme nu dans l’art de 1800 a nos jours (Masculine/Masculine. The Nude Man in Art from 1800 to the Present Day)

Victoria Hobday

*Please note that this review includes images of male nudity.

In September the Musée d’Orsay opened its autumn and winter exhibition Masculin/Masculin: L’homme nu dans l’art de 1800 á nos jours. This exhibition follows a similar one last year at the Leopold Museum in Vienna, Nackte Manner (Nude Males), which brought together a number of important works from 1800 to the present day. The president of the Musée d’Orsay, Guy Cogeval, decided that ‘nude males’ as a subject was a genuinely under-examined topic. With seven new curators who had recently joined the museum, he decided that it was timely to examine the same theme—but from a French standpoint. This did not mean limiting the works to French artists, but that the theme of masculine nudity was curated from a French perspective. How this differs from the ‘Germanic approach’—as the Musée d’Orsay catalogue describes the Leopold’s exhibition—is hard to imagine. I did not have the opportunity to compare the two but it would have been an interesting exercise in ‘Euro-perceptions’ of national stereotyping. I am still wondering what makes this exhibition particularly French apart from the liberal sprinkling of Pierre et Gilles works seen from one end of the exhibition to the other.

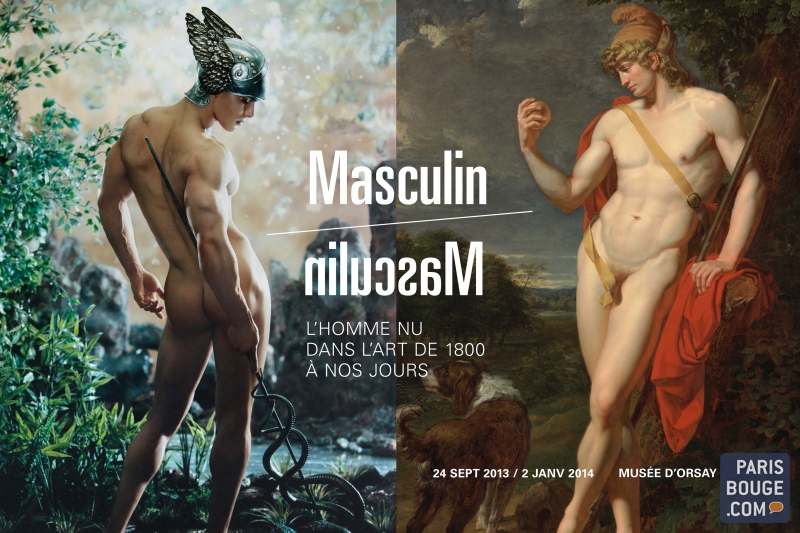

The exhibition is promoted by two large reproductions of works from different centuries (Fig. 1): Pierre et Gilles’ recent painted photograph entitled Mercure (Mercury) (2001) (Fig. 2) and the eighteenth-century painting Le Berger Paris (The Shepherd Paris) (1787) by Jean-Baptiste Frédéric Desmarais, (Fig. 3). The intention here is apparently to emphasise the fact that this is an exhibition that is centered on the male nude by the mirroring of these two nude male figures. Although from different modern eras they both make reference to the classical body in their standing poses and subjects. Interestingly the physique of the Pierre et Gilles Mercury is idealised in a very contemporary way: the muscular shape of his arms give the impression of many hours spent labouring at the gym rather than at manual tasks. Desmarais’ Paris, on the other hand, conforms to the classical canon revered in French nineteenth-century art. In this way the two figures, although similar in pose and fleshiness, subtly flag changing interpretations and attitudes to the aesthetics of the male nude that are explored by the exhibition.

Fig. 2. Pierre et Gilles, Mercure, 2001, (model Enzo Junior). Photograph and paint, 117.3 x 87 cm. Collection Pierre et Gilles, courtesy of Galerie Jérôme de Noirmont, Paris. Fig. 3. Jean Baptiste Frédéric Desmarais, Le Berger Paris, 1787. Oil on canvas,117 x 118 cm. Ottawa, Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada.

The different themes that structure the exhibition include those that one might expect to find: ‘the ideal’, ‘the heroic’ and ‘athleticism’; and others that are more surprising and rewarding, such as: ‘in nature’, ‘in pain’, and ‘the glorious body’.

The catalogue introduction limply attempts to stir up controversy by employing words like ‘audacious’ and ‘great importance to the history of art’ and, in case we still don’t realise how radical is the theme of the male nude, much is made of the number of exhibitions on the female nude and the historical neglect of the male nude. Yet although the idealised physiques and frequent androgyny of some of the figures in late nineteenth-century paintings are examined and discussed in the catalogue, the clearly erotic nature of the male body is only mentioned in passing. What is needed is a fuller account of such topics as homosexuality and art, the application of the gay kitsch aesthetic, pop culture and the male nude, and the history of the male gaze applied to the male nude subject. Such topics are only sketchily dealt with in the catalogue and passed over or ignored in the wall texts. The curators have emphatically pulled their punches: the topic of homoerotica is hardly mentioned in the catalogue and works that could be so described are confined to a small closed-off space with warnings. (These are repeated on the website: ‘Please note that some of the pieces presented in the exhibition may be shocking to some visitors (particularly children’).

Of more interest to the organisers are topics like the importance of the male nude as a measure of beauty and virility, which is discussed in the catalogue essay by Phillipe Comar. He writes of the influence of the work of Polyclitus, whose Doryphoros or spear-carrier was called the ‘Canon’, the embodiment of ideal proportions expressed mathematically in bronze. This canon still dictates many of the themes that can be seen in this exhibition. There is the focus on the athleticism of the male body, the attention paid to the form of the muscles, in interest in twisted poses or contrapposto, and the celebration of the young but physically mature body. The development in classical Greece of this classical model from the early Kouros of Paros to the Hermes of Praxiteles is only lightly touched upon in the early part of the exhibition but is more fulsomely explored in the catalogue essays. This is in keeping with the focus on the nineteenth century to the present day, so that we only see nineteenth-century copies of classical sculpture. Given the access that the Musée d’Orsay has to the Louvre it seems a shame that the original classical pieces could not have been used as the starting point.

Fig. 4. Edmé Bouchardon, Faune Barberini, copy after the antique, 1730. Marble, height 184 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Instead the exhibition begins with a small room with an eighteenth-century French copy of the Barberini Faun by Edmé Bouchardon (1730)—in fact from the Louvre (Fig. 4) (the original is in Munich). The combination of man and animal is emphasized in the sculpture by the tail at the back, the pointed ears and the panther skin that sits behind and across the figures left arm. This drunken sleeping figure has prominently exposed genitals framed by his legs, which seems strangely unrelated to the paintings that surround it. This include a number of dark nineteenth-century paintings that dwell on those religious subjects that most easily adapt to the display of the nude male, especially Saint Sebastian. Saint Sebastian figures throughout the exhibition, beginning with large seventeenth-century works by Georges de La Tour and Guido Reni. These works are the complete opposite of the Faun, as their draperies and contorted poses are constructed to display the body of the saint, but emphatically not the genitals. The effort taken to hide the male genitalia causes them, paradoxically, to become the primary concern of these images. Indeed, the exhibition as a whole seems to be a little coy about the way it celebrates the male body without drawing undue attention to genitalia.

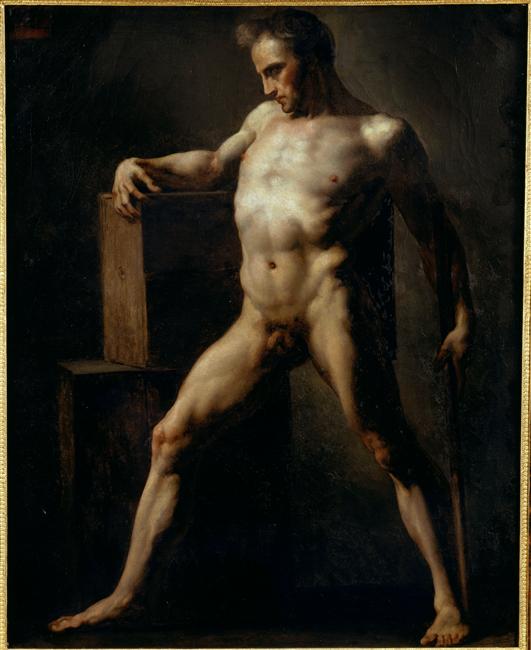

Fig. 5. Théodore Géricault Étude d’un homme, c. 1808–12. Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts.

In the second room there is a small oil study by Théodore Géricault (1808–12) (Fig. 5), which, although modest in size (c. 40 x 50 cm), is one of the gems of the exhibition. The sitter is a barrel-chested adult with a fleshy physique who stands with his bowed head in profile, the light striking his torso. His legs are stretched wide to emphasise the musculature of his legs. He holds a wooden pole in one hand behind him, a common studio prop that could stand in for a torch, spear or staff, while his other arm leans on one large timber box balanced on another. The use of male models in the studio is shown through a number of such studies but this is particularly powerful. Gericault specialised in painting the male body, often in violent or extreme poses, and only rarely did he paint women, apart from a handful of erotic studies.

The difference between the poses of male nudes and those of female nudes is one of the more striking aspects of the exhibition. Throughout the exhibition one notices there are poses that show off the muscular nature of men, the suppleness of youth and the surrender of martyrs. It is a very different overall effect to the supine women or women adorned that one finds in many of the adjoining galleries in the Musée d’Orsay. Later in the exhibition there is a marvellous large nude self-portrait by Lucien Freud, Reflection (1993) (Fig. 6) that echoes Gericault’s study in the focus on the body and the background void. It is an accomplished work that again shows the mature male body in a cool palette. His flesh is picked out against the darker taupe colours in the background by the stark overhead cold northern light. His arm raised with palette knife and foot forward imitates the adlocutio pose favoured in classical sculpture. The sockless shoes and the masterful loose paintwork convincingly undercut the heroic pose.

Fig. 7. Hippolyte Flandrin, Jeune home nu assis au bord de la mer, study, 1836. Oil on canvas, 98 x 124 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Hippolyte Flandrin’s Jeune Homme nu assis au bord de la mer (nude young man sitting next to the sea) (1836) (Fig. 7) is an anchor point for a number of works in the ‘In Landscape’ room. It shows both the dominating neoclassical style that influenced French artists in the first half of the nineteenth century and also provides the inspiration for two other photographic works that are shown in the exhibition. One is an early work by Wilhelm von Gloeden: Cain, Taormina, Sicily (1911), and the other is a work by Robert Mapplethorpe: Ajitto (1981) (Fig. 8). What is interesting about these three works is the repeated meditative self-contained pose of the model and the subtle differences in effect. The black and white Mappelthorpe photograph of an Afro-American model is the most sexualised; the model’s genitals are see backlit and in profile, changing the emphasis of the form. The painting by Flandrin, who was a disciple of Ingres, is more circular in composition. The figure is folded in on himself, giving the appearance of melancholic self-absorbed youth. The landscape serves to emphasise the isolation of the figure. Deep shadows outline the curve of the model’s back and hands but also mask most of his face with the exception of his right eye. Although Flandrin has painted the figure in an idealised neoclassical manner the effect is strikingly human and emotional. The juxtaposition of these three works demonstrates the changing attitudes towards the male body; even with the repeated pose of the figure there is a growing sexualisation being explored in the modern era.

Fig. 8. Robert Mappelthorpe, Ajitto, 1981. Gelatin silver print, 45.7 x 35.6 cm. The Robert Mappelthorpe Foundation.

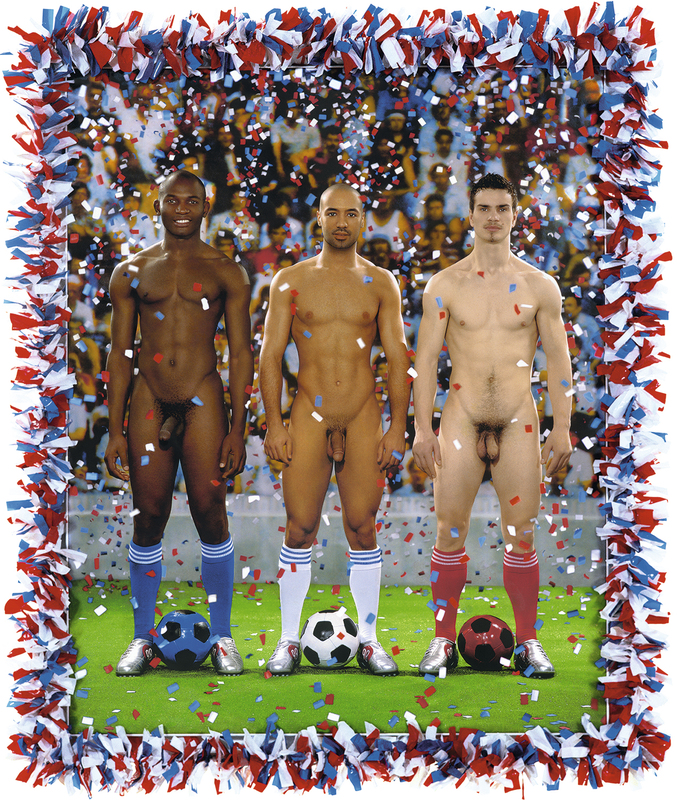

In the second part of the exhibition there is an increasing amount of photography, particularly in the section that concentrates on athleticism. Here we find Pierre et Gilles’ strongest work, Vive la France (2006) (Fig. 9). The bounced-up lighting of sports photography and the colours of France are used to frame three nude soccer players, one black, one white and one North African. The tricolour of the French flag is echoed in the use of the raffia pompom-like frame, and in the three different coloured soccer balls and the socks of the players. More importantly the different skin colours of the players, who all face the camera naked apart from socks and boots, is a clear comment on the multicultural nature of France that is often only acknowledged in sport.

Fig. 9. Pierre et Gilles, Vive la France, 2006. Hand painted photograph, inkjet print on canvas, 125 x 101 cm. Private collection.

The introduction of photography serves to counteract the often ponderous academic paintings of the early rooms—shiny-skinned youths painted in a dying light—by introducing the nineteenth-century interest in the scientific recording of physical motion. Here we see Eadweard Muybridge’s Nude Male Pole-vaulting (1887) and Two Wrestling Nude Men (1887) (Fig. 10), a study of men wrestling naked and falling to the ground. These photographs, which inspired later artists such as Francis Bacon, allow the exhibition to move into a more exploratory mode. One of the more interesting works is the series of photographs from the Kinsey report on sexuality (currently the subject of a mainstream movie): a small series of photographs that show that stepping off the main path onto the soft verges of a theme can open up unexpected avenues.

Fig. 10. Eadweard Muybridge, Two men wrestling, 1887. Photographic proofsheet, héliogravure, 16.5 x 43.5 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

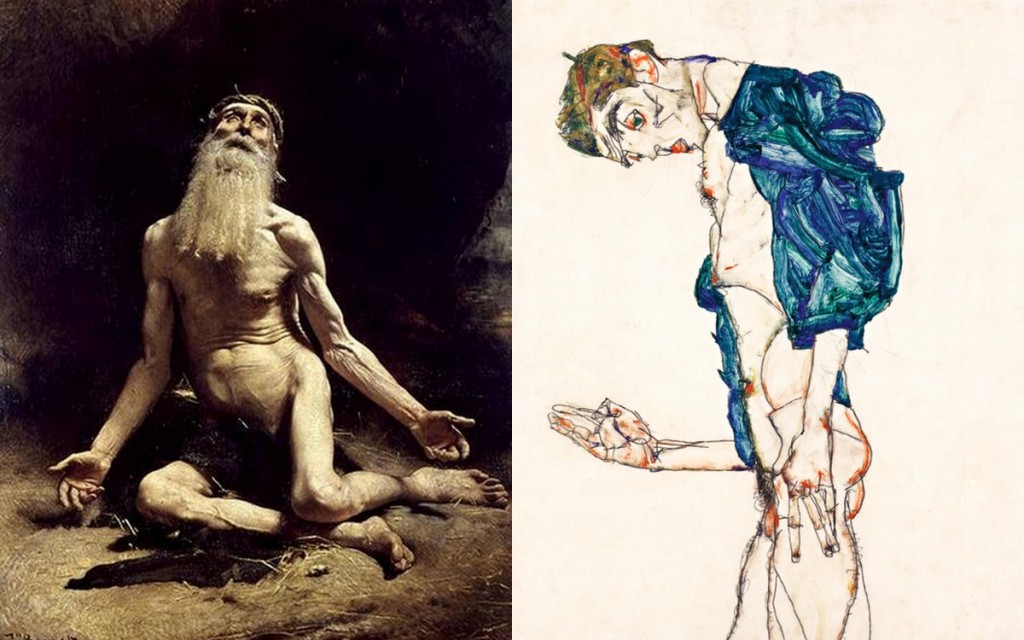

In the rooms that centre on the theme of ‘In Pain’ and ‘In Landscape’ there are more broad strokes in the curatorial choices. As with previous exhibitions at the Musée d’Orsay this exhibition describes through extensive wall texts the curatorial direction in the thematic rooms in such a way as to appeal to a wider and predominantly ‘touristic’ audience. The thematic approach frees the curators to mix period, medium and style and through this pastiche create new dialogues between works. This is done with varying degrees of success. In the room devoted to ‘In pain’, we find works from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries selected to show aspects of the male nude that range from realism to the description of mental anguish. The realism of Leon Bonnat’s Job knocks the corners off the earlier heroic perfectionism and instead serves up flesh that is dirty, cold and aged (Fig. 11). The contorted forms of the Egon Schiele’s self-portraits on paper (Fig. 12) gives the room a wider interpretation of the body beyond just the physicality of the male ideal. Schiele uses the angularity of his light frame to expose his own delicate mental state, described in the awkward pose and the enlarged eyes, his use of redrawn pencil lines and the shock of hair that contrasts with the emaciated body.

Fig. 11. Léon Bonnat, Job, 1880. Oil on canvas, 161 x 129 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Fig. 12. Egon Schiele, Homme nu (autoportrait á la chemise bleue et verte), 1913. Pencil and gouache on paper, 47.1 x 31.2 cm. Vienna, Leopold Museum.

The last section, the one with warnings about possible offensive material, flirts with matters missing from the body of the exhibition. Here a photographic work by French artist Orlan entitled The Origin of War (1989) that riffs on the Courbet painting The Origin of the World is simple, humorous and poignant (Fig. 13). The curators here let fly with twentieth-century offerings that present more confronting and transgressive images of the male body, including images that pertain to homoerotic and sadomasochist imagery. The smallness of the space and the separating partition are disappointing and give this section the feeling of a slightly guilty afterthought. Not surprisingly this was one of the more crowded rooms.

Fig. 13. Orlan, L’Origine de la Guerre, 1989. Colour print, 87.3 x 102.3 cm. Courtesy of Orlan and Gallery Michel Rein, Paris.

Masculin/Masculin misses the opportunity of discussing some of the deeper and more controversial meanings and interpretation of the male nude, especially given the auspicious timing of the approval of gay marriage in France last spring. Whether or not this exhibition was seen as an opportunity to engage with a gay audience it has given the viewing public the opportunity to see some unusual examples of works by a wide range of artists. The diversity of the works is exceptional, although I would have preferred rather fewer by Pierre et Gilles. I suppose they serve to wave the French flag, and are suitably un-Germanic.

© Victoria Hobday 2013