For Auld Lang Syne: Images of Scottish Australia from First Fleet to Federation is on at the Ballarat Art Gallery until the 27th July 2014.

Victorian regional galleries are more than pulling their weight when it comes to hosting exhibitions in centres beyond Melbourne, as Genius and Ambition: The Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1768-1918 at the Bendigo Art Gallery has recently proved. Ballarat Art Gallery is playing host to For Auld Lang Syne: Images of Scottish Australia from First Fleet to Federation, curated by Alison Inglis and Patricia Tryon Macdonald.

The sheer scale of the exhibition, which surely must make it one of the — if not the — most significant exhibitions of Scotland-related material in Australian history, makes it noteworthy. Spanning four gallery spaces of the Ballarat Art Gallery, the exhibition is co-ordinated under five main subject areas. In ‘Science and Discovery’, Scottish contributions to the exploration of Australia and the documenting of its physical and human geography are explored. ‘Establishing a New Society’, pays homage to some of the driving figures establishing ‘civilisation’ in Australia. ‘Ingenuity and Enterprise’ includes several portraits of early homesteads, standing like solitary sentries on the frontiers of a new land, bastions of civilisation advanced against the threat of the great vacant uncivilisation of the Australian interior. ‘Taste and Tradition’ offers an impressive display of Australian-owned paintings on Scottish subjects, while ‘Scottish Artists in the Antipodes’ should lead viewers to question whether Scottish artists merely transplanted modes of seeing Scotland to seeing Australia. Finally, ‘Caledonia Australis’ shows a number of objects illustrative of the fostering of Scottish national identity in Australia.

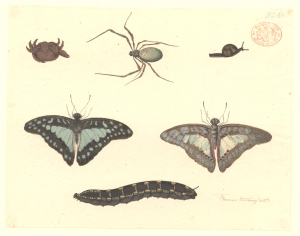

Thomas Watling, A crab, a spider, a snail, two butterflies and a caterpillar, 1792-1797< Natural History Museum, London

The range of material in the exhibition is breathtakingly large, extending from the purely scientific (the terrestrial charts in ‘Science and Discovery’) and ethnographic (Robert Neill’s Indigènes des deux sèxes (1827) in the same section) to pieces that, while ostensibly being ‘scientific’, reveal the kind of visual experience typical of the artist (for example, Thomas Watling’s Goo-roe-Goo-roe, showing a kind of mounting board of a crab, a spider, a snail, butterflies and a caterpillar). ‘Establishing a New Society’, dense in portraits of military and religious figures, provides an important conspectus of portrait styles of the nineteenth century, and opens questions about the ways in which the sitters, some of them now little more than names, represented themselves to posterity. ‘Caledonia Australis’’ bagpipes, sgian dubh, scrimshaws, goblets made of horn, and newspaper announcements all offer eloquent testimonies to the lived experience of Scottishness in Australia.

The rooms of paintings offer particularly rich pickings. ‘Ingenuity and Enterprise’s homestead ‘portraits’ include some magnificent paintings, including Von Guérard’s View of the Gippsland Alps (1861). William Handcock’s paradisiacal, almost tropical realisation of Ercildoune Homestead (1870), envisaging Australia as a kind of neo-Sri Lanka, forms a striking contrast with the Scottish Baronial interior of Werribee Park as imaged by Albert Charles Cooke in 1878. The material of ‘Taste and Tradition’ and ’Scottish Artists in the Antipodes’ will lead visitors to ask questions about the intersection between the visual tradition of an old Scotland in an old Europe and the terra nova of Australia. Waller Hugh Paton’s Dunfermline Abbey (1861) sees Scotland through the lens of European Baroque painting, particularly of Meindert Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis. John Carse’s 1876 Australian scene of Weatherboard Falls seems strikingly like Keeley Hallswelle’s The Heart of the Coolins (1886), a Scottish scene. John Mather’s Picnic Point (1886) and A Woolshed (1889) understand that Australian light is fundamentally different from Scottish light, and make no apologies for that. One sees the development of ‘naturalistic’ landscape painting at work from John Glover’s evident bewildered incomprehension of the Australian landscape to Von Guèrard studiously ‘scientific’ painting of it. Purely aesthetic questions will also offer themselves — what does Peter Graham’s Massacre at Glencoe tells us about the cult of the Sublime in European painting at the end of the nineteenth century? What does Gordon Coutts’ Fisherman’s Hut (1893) tell us about Australian reception of developments in contemporary French painting?

Top: J. H. Carse, The Weatherboard Falls, Blue Mountains), 1876

Bottom: Keeley Hallswelle’s The Heart of the Coolins (1886).

The central ‘argument’ of this exhibition is that the Scots helped make Australia. While this may seem self-evident, this is the first time the extent of that contribution has been made visible in an exhibition. One could argue that multiplicity of organising themes is both the strength and weakness of the exhibition. Such an approach is essentially ethnographic: objects are presented as specimens of Scottishness, like the natural history specimens in the ‘Science and Discovery’ section. This runs the risk of obscuring the multiple narratives of Scottish identity.

Given the diversity of material, and the thinnish assistance offered by text within the exhibition, the catalogue — itself a major work of scholarship — should offer those interested further food for thought.

© John Weretka 2013