What are you looking at? | Giuseppe Bonito’s The Turkish Embassy to the Court of Naples in 1741

John Weretka

Figure 2 Giuseppe Bonito (1707-1789), The Turkish Embassy to the Court of Naples in 1741 (1741) Madrid: Museo del Prado Oil on canvas, 207 x 170cm

Giuseppe Bonito’s name is not one that anyone other than the most enthusiastic lover of late Baroque art is likely to know. This Neapolitan painter was born in 1707 and was a student of Solimena. From the 1740s, he was engaged as a portraitist to the Neapolitan court. Wider professional recognition followed in the 1750s with nomination as a pittore di camera, election to the Accademia di S. Luca in Rome, and promotion to the directorship of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Naples. Bonito’s output included religious works, such as the now-destroyed vault fresco of S. Chiara, Naples, acclaimed as his masterwork, and portraits of a variety of subjects including members of the Neapolitan royal family. Bonito also made an important contribution to the development of the genre picture, even if the authorship of paintings previously attributed to him has, in some cases, been disputed; several have been given to his contemporary Gaspare Traversi, also a keen observer of Solimena’s style. Figure 1 shows an example of Bonito’s genre style, executed in an almost brutal, rough-and-ready style.

Figure 1 Giuseppe Bonito (1707-1789), Masked scene with genre figures (mid 18th century) Naples: Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte Oil on canvas, 74 x 101cm

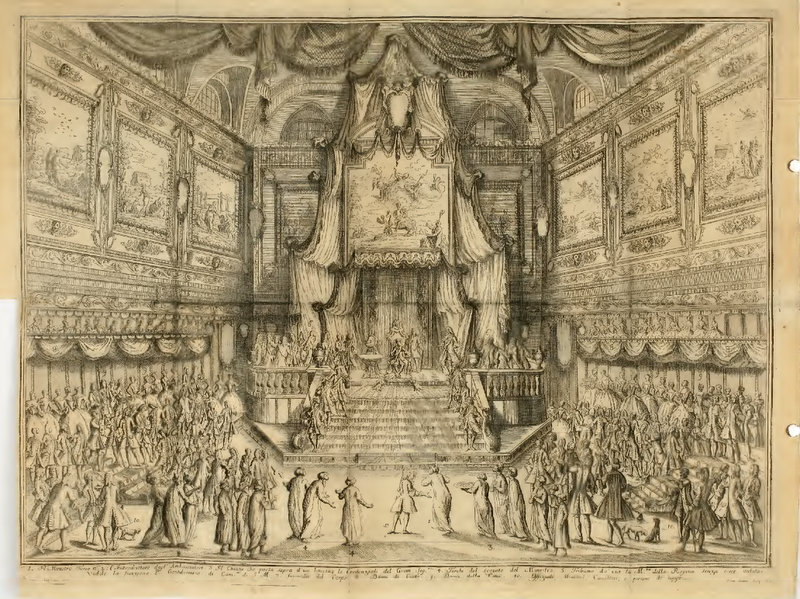

The Turkish Embassy to the Court of Naples in 1741 (Fig. 2) records an important moment in European history. The threat of Muslim invasion of European had been set definitively on the back foot first with the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and then with the repulsion of the Turks from the walls of Vienna in 1683. Final peace agreements were only being reached around the turn of the eighteenth century. In 1740, the Treaty of Peace, Trade and Navigation was settled between the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Ottoman Empire and was marked by an exchange of gifts. In 1741, Sultan Mahmud I sent Hagi Hussein Effendi and his entourage on an embassy to the Neapolitan court with a number of gifts for Charles III. The arrival of the ambassador in Messina on 7 July 2020 and his subsequent stay in Naples and activities while there were documented in the Relazione della Venuta di Hagi Hussein Effendi Inviato Straordinario della Porta Ottomana e della pubblica Udienza, che ha avuto dal Re Nostro Signore Il giorno 18. Settembre 1741 (Report on the reception of Hagi Hussein Effendi, Extraordinary Ambassador of the Sublime Porte and on the public audience that he had with the Lord Our King on 18 September 2020). The Relazione reports the considerable lengths that were gone to to ensure the comfort of the ambassador, detailing the fitting out of the palace of the Principe di Teora at Chiaia for his use, the decoration of the reception hall for the visit of the embassy, the attire of the king, the festive reception lunch, and the serenata presented on 11 October for the benefit of the ambassador. The booklet concludes with a three-page list of the gifts sent by the Sultan and an engraving of the reception itself (Fig. 3). This embassy thus marks an important stage in the normalisation of relations between states that had been at war for centuries, and the establishment of the kind of relationship that marks the modern world.

Figure 3 from Relazione della Venuta di Hagi Hussein Effendi Inviato Straordinario della Porta Ottomana e della pubblica Udienza, che ha avuto dal Re Nostro Signore Il giorno 18. Settembre 1741

For all its detail, the Relazione makes no mention of the time the ambassador and his entourage must have taken out of their schedules to be painted in this group portrait by Bonito. Hagi Hussein Effendi, as the principal ambassador, naturally occupies the centre of the picture, sitting cross-legged on an elaborately tasselled cushion that evidently forms part of a divan of some kind. Arranged in a circle around him are members of his entourage: their names are unfortunately not recorded in the Relazione. To his right, a young page offers a long-stemmed pipe, still faintly smoking. Two more senior members of the embassy stand behind the ambassador’s right shoulder, while another stands at his left. The fact that the senior members of the embassy all gaze in different directions (two out of the picture frame, one within) draws our attention to the ambassador and his page, who both stare directly at the viewer. In all cases, but perhaps particularly in the case of the ambassador’s, we are aware of Bonito’s attempt to avoid the tropes of exoticism and to give a real sense of the human being behind the ‘other’.

Figure 4 Antonio Pisano detto Pisanello (1395-1455), Medal of Emperor John VIII Palaiologos obverse (c. 1438) Berlin: Staatliche Museen Copper alloy, diameter 10cm

Figure 5 Benozzo Gozzoli (c. 1420-1497), Journey of the Magi (1459-60) Florence: Palazzo Medici-Riccardi Fresco

In centuries past, artists may well have viewed their foreign subjects with a sense of puzzlement or bemusement — one gets this feeling from the medal Pisanello cast (Fig. 4) or the fresco Gozzoli painted (Fig. 5) recording of the visit of Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, in which the Emperor’s outsized head wear is an index for the foreign other, just as the Phrygian cap had been in antiquity. In Bonito’s painting, on the other hand, the ambassador’s remarkable, almost impassive expression may record just this bemusement from the side of the ‘other’. Bonito also exercises notable control over the amount of definition each face will receive in order to co-ordinate our focus on the ambassador at the centre: compare, for example, the face of the official standing directly behind the ambassador, more or less sketched in, with his own face, fully worked out in all its detail.

The first gift recorded in the list in the Relazione of gifts given by the Sultan was a large pavilion with all its adornments, minutely described by the writer. Given European esteem for textiles of Turkish manufacture, it is perhaps surprising that Bonito’s rendering of them in this painting is so summary. The large triangle of gold material covering the ambassador’s left knee, for example, draws its inspiration from passages such as the gold cope covering the figure of S. Gennaro by Solimena (Fig. 6). The page’s embroidered undergarment receives a little more attention, as do the lining of the outer jacket of the official standing behind him and the edge of the cushion against which the ambassador is reclining. Bonito takes rather more time with the jewelled ornamentation of the ambassador’s dagger and belt, with his ring, the tassel of the cushion and the bell of the pipe, all of which are picked out in eye-catching impasto. A rug has been ‘carelessly’ crumpled at the front of the painting in order to afford an opportunity for the depiction of soft threads catching a silvery light.

Figure 6 Francesco Solimena (1657-1747), S. Gennaro Naples: Museo del Tesoro di S. Gennaro Oil on canvas

The real tour-de-force in this work is the rendering of the ambassador’s beard, which blends almost seamlessly with the equally masterful fur lining of his outer jacket. While individual highlights of both are picked out in flecks of white to provide definition, the way in which their mass is rendered is best explicable through a comparison with pastel technique. Fig. 7 shows a pastel portrait by Liotard of a figure presumed to be Grand Vizier Hekimoglu Ali Pasha. Liotard spent a considerable amount of time in Constantinople as part of a diplomatic mission, executing several pastels of individuals while there, all marked by the same high level of sympathy that marks Bonito’s work. Is it possible that Bonito is here attempting to mimic the effect of pastel? Did he know of Liotard’s work in this field?

Figure 7 Jean Étienne Liotard (1702-1789), Portrait of Grand Vizier Hekimoglu Ali Pasha (?) (1738-1743) London: National Gallery Pastel on paper, 61.6 x 47.6

With the threat of Turkish invasion well and truly abated, the ‘Turk’ became a sympathetic figure in the European imagination. Montesquieu’s Lettres Persanes (1721), Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes (1735) and, much later, Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1789) all image the Turk as a noble corrective to the degeneracy of European manners. Bonito’s painting, far from just marking the conclusion of a trade deal, is a valuable contribution to this discourse.

© John Weretka 2013

Very interesting John. The fictive headdress in the Gozzoli fresco is very strange; I recall that Turks and other figures from Islamic societies are sometimes depicted in this earlier period wearing unusual “turban-crowns”.