J.W. Power: Abstraction – Création Paris 1934

Reviewed by Sheridan Palmer

J.W. Power: Abstraction – Création Paris 1934, Sydney University Art Gallery, open now until January 26th, 2013.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the J. W. Power bequest to the University of Sydney, an exhibition and catalogue produced by the University Art Gallery and Power Institute revives Power the artist, who in Australia has until now been largely eclipsed by his philanthropy. The Power Bequest, at the time close to £2,000,000, was initially announced in 1961 and was intended to support the study of the Fine Arts and in particular the understanding of contemporary art. It came with a remarkable archive including Power’s papers — now held at the National Library of Australia — and some 1170 of Power’s own works of art. These range from his more juvenile Edwardian studies executed in Sydney and Melbourne to mature, highly finished works from his expatriate period. The collection also includes around 200 vignette oil sketches and studies. Many of these reveal just how accomplished an artist Power was and from this trove the senior curator of the University Art Collection Dr Ann Stephen and co-curator A. D. S Donaldson have recreated Power’s 1934 solo Abstraction-Création exhibition. Created during the late 1920s and early1930s these works have rarely been seen since 1963, when the pro modernist Englishman and director of the NGV Eric Westbrook had decided they should be shown at the National Gallery of Victoria. Using the artist’s own plan of the layout (Fig. 1, Plan de l’Exposition, gouache, pencil and ink on paper) this exhibition at the University’s Gallery in the Old Quadrangle, though modest in size, creates an effective visual parallel with Power’s original show at the Abstraction-Création Gallery, then located at 44 Avenue Wagram in Paris, just off the Champs Elysee. The exhibition is a remarkable testament to an Australian expatriate whose life and art deservedly warrants reevaluation.

John Joseph Wardell Power was born in Sydney in 1881 and left Australia for England after graduating with a Bachelor of Medicine from the University of Sydney in 1904. He continued his medical studies in London and later Vienna, before enlisting in the First World War. As the grandson of William Wardell, the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne, and the son of a distinguished surgeon and founder of the M.L.C. insurance company, Power was by inheritance a wealthy man, and by the end of the war chose to abandon medicine and devote his life to art. It was a period in which Europe was experiencing radical political and cultural change, and Power, by nature a restless cosmopolitan, settled comfortably into the mood of this milieu, gravitating towards some of the most avant-garde cohorts operating in London, Paris and other culturally active centres throughout Europe.

Fig. 2, Fernand Léger’s Atelier Moderne studio 1924, J. W. Power fifth from left, silver gelatin on paper 16.5 x 35.5 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

For many Australian and New Zealand artists in the late nineteenth and first decades of the twentieth century Europe was de rigueur as a destination—Hilda Rix Nicholas, Hugh Ramsey, George Lambert, Margaret Preston, Nora Heysen, Agnes Goodsir and Max Meldrum, to name a few, studied and worked in England and France for many years—but most eventually returned bringing their acquired aesthetic innovations with them. But for J.W. Power, whose cultural immersion especially in Paris was personally rewarding, highly productive and professionally successful, the thought of returning to provincial Australia was unimaginable. Moreover, Power could afford to move freely between England, Brussels and France, attend ateliers in Paris and lectures at the Sorbonne, amass an art collection that included Lèger, Ozenfant, Gris, Gleizes, Picasso and Diego Rivera, and absorb many of the fashions and influences of the day. He nevertheless ‘understood that to play the foreigner in order to be included’ was both necessary as well as suiting his temperament.[1] His work ‘Ypres’ (1917), made during the war, shows an amalgam of stylistic influences, such as those of the English Vorticists Edward Wadsworth and Paul Nash and the dynamism of Claude Flight, Ian Macnab and artists associated with the symbolist abstractionist movement. With a keen interest in music and theatre, and inspired by ‘the relationship between colour and music’, Power may also have been influenced by the British stage designer Edward Gordon Craig’s striking modernist designs. It was after all the time when artists such as Picasso and Lèger were designing for Eric Satie and Sergei Diaghilev.

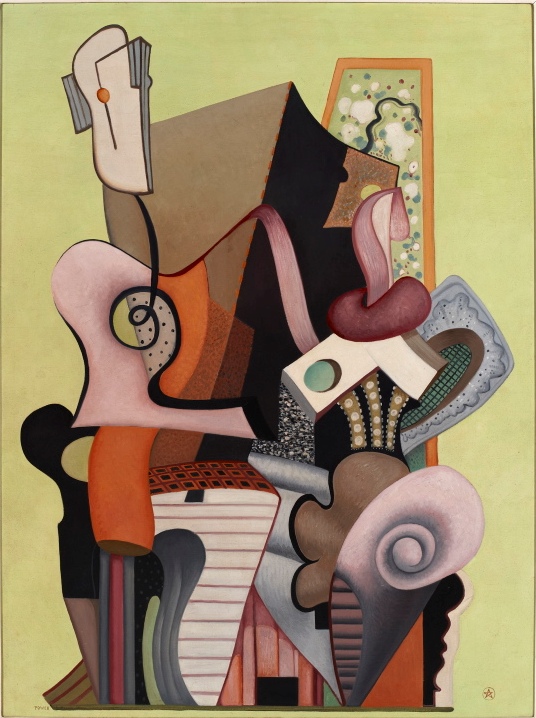

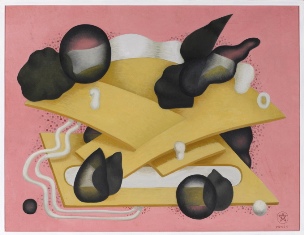

By the early 1920s, Power had emerged as a progressive artist associated with the London Group of British modernists and by 1924 he was attending Fernand Lèger’s ‘influential Parisian teaching atelier Academie Moderne’ (Fig. 2). His painting had developed a tightly structured, closed format and a highly finished formalism based on a post Cubist and geometric Purism. His palette ranged from ‘refined tonalities’ to passages of vibrant colour, a rich anatomy of connective ribbons, tubular limbs and organic shapes that he juxtaposed with decorative patterning and muted, sensual, coralline forms. The painting Conversation (1931-32) (Fig. 3) engages a high-pitched palette with a strong structural design. The effects of Power’s analytical quasi-figurative abstractions are sophisticated as well as suggestively playful, parodic and sexual, and reveal the influences of Juan Gris, Ozefant, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Lèger, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, artists he greatly admired or personally knew. His art was also constructed according to a sophisticated analysis of the relationship of painting to geometry, which he had developed over a period of some ten years and published as Elements De La Construction Picturale in 1933. This treatise joined other publications on the ‘intellectual tradition for abstraction’ and was recognized by artists and critics as providing ‘a post cubist synthesis capable of reconciling the sensorial with the ideal’.[2] His painting Paysage (1934) in which structures float in a galaxy of abstraction and colour, evoke what Power termed the ‘moving format’ (Fig. 4).

J.W. Power’s paintings, journals and photographs provide an intriguing insight into the avant-garde of the inter-war period. His association with the Abstraction-Création group from 1931 to 1936 put him in the company of some of Europe’s most important modernists such as Jean Arp, Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Lucio Fontana, Jean Helion, Barbara Hepworth, Albert Gleizes, Kandinsky, Kupka, Mondrian, Nicholson, Picasso, Schwitters, and Vantongerloo. As the only Australian of the chosen ‘new lot’—though Ann Dangar appears to have been associated through Albert Gleizes—and one of the group’s most consistent members Power held a seminal position within both the group and the wider artistic landscape. The essays, in the elegant, cloth bound hard cover catalogue include a superb analytical reading of Power’s numerous studies and painting of Apollo and Daphne by Virginia Spate, and an important essay by the art historian Gladys Fabre, translated for the first time, on the artistic climate of Paris in the 1930s. Together with Stephen’s and Donaldson’s valuable contributions these essays prove there is much to be revisited and exhumed from this period. In 1931 Power wrote that ‘Surrealism holds the floor, that is amongst the young and thoughtful ones…’ and his critique of the modes and movements offer a vital view of the continental world as a mirror to what would begin to develop in Australia by the late 1930s, with artists like Eric Thake, Rah Fizelle. Crace Crowley, Ralph Balson. Historically contextualizing J.W. Power’s presence within the core of Europe’s avant-garde activity is well dealt with, but to what extent Power exerted any influence upon the development of Australia’s own artistic world remains illusive. This is a question Ann Stephens and A.D.S Donaldson pose when they claim that Power ‘is the most important figure in our early avant-garde and his life and work raise questions for our art history’.[3]

Had Bernard Smith, the inaugural director of the Power Institute, made a closer reading of Power’s art and his position within the avant-garde formations of London and Paris (he did make preliminary investigations regarding the expatriate in 1963 and enquire in 1968 to the famous Parisian art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler about Power) he might have made more of this expatriate artist. Rather, as is noted in the catalogue essays by the curators, he consigned Power the artist to an art historical closet. Perhaps Smith was affected by the need to keep the two sides of Power’s estate separate for reasons of university politics, his concern with implementing Power’s will, the establishment of a new Institute of Fine Arts — the Power Institute — and the application of the term ‘contemporary, which for purposes of definition was deemed as ‘art that was not more than twenty years old at the time … or was the work of living, and contemporary artists’.[4] Clearly, the contemporary fully occupied Smith and Power’s art (he died in 1943) was outside the prescribed boundary of twenty years. Moreover, Smith had a new body of avant-garde material, the first of the new Power acquisitions to deal with. His relegation of Power as an artist to a footnote in history nevertheless provides us with the opportunity of another corrective programme, as initiated by Stephen and Donaldson in their rehabilitation of this remarkable, cosmopolitan expatriate figure.

This small but excellent exhibition will travel to the National Library of Australia in Canberra from 25 July to 2 November 2014, where additional Power-related material owned by the Library, including 54 sketchbooks, will be added. It will then be exhibited at Heide Museum of Modern Art from December 2014 to January 2015.

© Sheridan Palmer 2012

List of images.

Fig. 1. J.W. Power Plan de l’Exposition 1934 gouache, pencil and ink on paper 62.8 x 50 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

Fig. 2, Fernand Léger’s Atelier Moderne studio 1924, J. W. Power fifth from left, silver gelatin on paper 16.5 x 35.5 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

Fig. 3. J.W. Power, Conversation 1931-32 oil on linen 112.5 x 84.2 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

Fig. 4 J.W. Power, Paysage (Landscape) 1934 oil on linen 50.9 x 66.3 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

Fig 5. J.W. Power, Tête (Head) 1931 oil on linen 94 x 45.8 cm. JW Power collection, The University of Sydney, managed by Museum of Contemporary Art

[1] Sophie Levy quoted in Donaldson, A.D.S and Ann Stephen, J.W. Power: Abstraction–Creation Paris 1934, Sydney, Power Publications in conjunction with the University of Sydney, 2012, p. 33

[2] Lionel Venturi, quoted in J.W. Power: Abstraction–Creation Paris 1934, p. 22

[3] J.W. Power: Abstraction–Creation Paris 1934, p. 10

[4] Report by Professor John White, University of Manchester, who was invited to interpret the bequest and develop a plan of implementing the wishes of J.W. Power within the University of Sydney’s Arts Faculty.