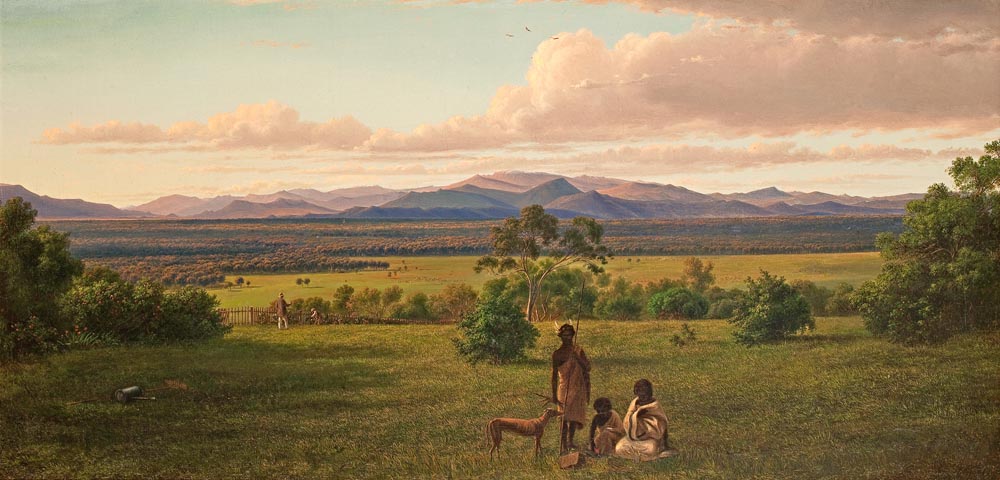

A hidden story: Eugene von Guérard’s Mr John King’s station, 1861

Ruth Pullin

Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861, Oil on canvas laid on board, 40.7 x 83.9 cm, Private collection, England

With the closing of the National Gallery of Victoria’s touring exhibition Eugene von Guérard: nature revealed in Canberra in July of this year it is timely to reconsider rarely seen works in the light of the close analysis made possible by the exhibition. The enigmatic Mr John King’s station 1861 (Fig. 1), not seen in Australia since 1980 and now returned to its private owners in the UK, is a work that, with its inherent ambiguities and seemingly unresolvable questions, invites renewed attention. Nothing is quite as it seems in Mr John King’s station. Conceived within a compositional and ideological framework derived from the classical European landscape tradition the painting appears to endorse the values and the social and economic concerns of the European landowner. But from within the parameters of this construct alternative realities concerning this place become apparent. The dark and suppressed history of war, massacre and dispossession associated with the European settlement of the region is both concealed and revealed in von Guérard’s landscape.

Eugene von Guérard’s portrayal of John King’s station is ostensibly a property portrait, painted in the tradition of the artist’s Western District homestead pictures. It portrays John King’s station Snake Ridge, an extensive run situated in Gippsland on the La Trobe and Glengarry rivers between Traralgon and Rosedale, and stretching northeast towards what was, in 1860, Angus McMillan’s property Bushy Park. Von Guérard stayed at Snake Ridge on 18, 19 and 20 November 1860. He was en route to join Alfred Howitt and his party who were on a government gold prospecting expedition that would lead them along the Wonungarra, Wonangatta and Crooked rivers and into some of the most rugged, almost impenetrable country in the Australian Alps. An entry in John King’s day book for Sunday 18 November recording von Guerard’s arrival reveals that he was an expected guest. This, and the sketches and drawings von Guérard made on the property over the next two days, including two with extensive notes documenting colour, light effects, clouds and tree species, suggest that the painting, which remained in the collection of Mr King and his descendants until 1972, was a commission.

And yet this painting subverts our expectations of a commissioned homestead portrait. The homestead is notable for its absence. Rather it is the expansiveness of the lush and beautiful landscape that is celebrated, a landscape of fertile plains dotted with grazing cattle (being fattened for the Tasmanian market) that stretches towards the southern end of what is now the Australian Alpine National Park. John King’s custodianship of the land is signified only by the presence of two Europeans, presumably John King himself and his gardener, depicted attending to the roses growing along the picket fence that defines the immediate realm of European cultivation (Fig. 2). The European ‘owner’ of the property is relegated to the middle ground, his back to the viewer, and his gardener’s face is lost in shadow: their exchange constitutes an anecdotal vignette, as in a conversation piece; they play the role of mere staffage, anonymous figures in the narrative of the painting.

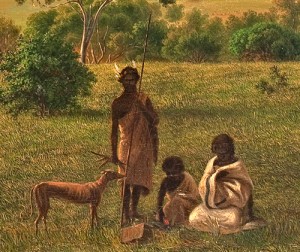

By contrast, and in a way that is atypical of homestead pictures that by their very nature are designed to celebrate the proprietorial achievements of a European landowner, the Kurnai (or Gunnai) man, woman and child and their dog take centre stage in this composition (Fig. 3). Placed in the immediate foreground they, the original custodians of this country, gaze out at the viewer. Whether by design or not the rather artificial positioning of the group in the landscape (and the painting) reflects the new ambiguities of their situation in mid nineteenth century Gippsland. As individuals they each represent aspects of their traditional and current realities. Poised and dignified, the young man stands strong and proud epitomizing the traditions of the Gunnai people: he presents himself formally in a possum skin cloak (fur side against his skin) and a white (cockatoo?) feathered headdress; he carries boomerangs, a club and a spear. Von Guérard may well have been aware of the role of the possum skin cloak as a signifier of identity and connectedness to country as a result of his close association with Alfred Howitt (who subsequently published an authoritative study of the Gunnai tribes and their customs) and it seems that von Guérard acquired a possum skin cloak at some stage during his time in Australia; it is now held in the Berlin Ethnological Museum.

The woman seated on the other side of the group, by contrast, is draped in a blanket, the blue lines along its edges identifying it as one of those issued by the newly formed Victorian government authority, the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines. Nicholas Thomas, writing principally of View of the Gippsland Alps from Bushy Park on the River Avon 1861 but with reference also to Mr John King’s station, observed the anomaly that saw the Gunnai people depicted on their land, yet dispossessed of it and subject to the paternalism of the very men (McMillan and, to a lesser extent, King) who had, less than twenty years earlier, been involved or complicit in the massacres of their people, one of which took place at Boney Point (where the Avon River meets Lake Wellington) in 1840–41.

The child also wears a government-issue blanket draped over one shoulder in the manner of the cloak worn by her father (the blankets had none of the thermal or water-resistant properties of the possum skin cloaks and so had a negative effect on the welfare of Aboriginal people). In front of her an empty satchel sits on the grass. Under magnification the dead parrot held by the child, its wings splayed open to reveal its brilliant colours—a detail not readily discernible to the naked eye—is revealed (Fig. 4 – see gallery below). It may be that the parrot has been presented to the group by the dog that, despite its evident European ancestry almost certainly belonged to the family group. Its thinness and the red collar it wears, Philip Jones has suggested, identify it as one the thousands of dogs of European descent that quickly became attached to Aboriginal groups. The significance of the bird, the focus of the child’s attention and yet painted at a scale that makes it almost impossible to see, is a mystery. With its wings spread open to expose its body, rather than closed as is typical for a dead bird, could it be that this beautiful, vulnerable and barely discernible bird is a metaphor for the unspoken recent history of this landscape and its people?

There are no clues in the composition as to how we are to make sense of the coexistence of the formally posed Aboriginal group and the two Europeans in this landscape. Each group is, apparently, unaware of the presence of the other; the Gunnai family is situated within the confines of the newly established domestic garden and yet they seem to inhabit a different realm. A vast psychological distance separates them from the Europeans who pursue their activities apparently oblivious to the silent presence of the Aboriginal family. Our attention is directed towards the Europeans by the disconcertingly large watering can and rake lying abandoned on the grass (Fig. 5). The late afternoon sun illuminates the two men while backlighting and shadows make it difficult to see the Gunnai people, despite their being in the foreground. The ambiguities extend to the management of the land itself: the vignette of small scale domestic gardening on land that had known European settlement for just twenty years, is set against country that has been managed by the local Gunnai people for thousands of years. In his recent book The Greatest Estate on Earth Bill Gammage describes the controlled burns used by Aboriginal people to encourage areas of fresh new grass that would attract game to open ‘necks’ of grassland that were, as here, screened by promontories of bushland that provided cover for hunters. This and the park-like character of the landscape so valued and frequently commented upon by the early settlers was the result of the land management practices employed by the original custodians of the land over time immemorial.

Fig. 8 Eugene von Guérard Carolin, Sketchbook XXIV, South Australia 1855, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 3, f. 84

Although von Guérard had numerous encounters with Aboriginal people in Gippsland and on other Victorian expeditions, there is no evidence that he observed this family group at the site. No figures appear in the drawing of the subject produced at the site on 19and 20 November (From Mr John King’s Station Snakes Ridge Gippsland 19 & 20 Nov 2020, 1860, Fig. 6). In extensive notes on the drawing von Guérard’s concern was to identify mountain peaks (Mt. Buller with snow, Mt. Wellington and Ben Cruachan), European plants (roses and Rubilla) and to record his impressions of colour. But his strong interest in Aboriginal culture is evident in a drawing he made just a few days after leaving John King’s station when he sketched a pair of Gunnai men paddling a bark canoe, a drawing annotated with explanatory notes and details of the paddle (Sketchbook XXXII, Gippsland 1860, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 11, f. 5, Fig. 7)—but in the case of Mr John King’s station it appears that the artist has ‘inserted’ the Aboriginal group into the composition. In the formality of their grouping they recall the photographs of Antoine Fauchery and others. But the model for at least one of these figures can be found, not in photography but in one of von Guérard’s sketchbooks: the child comes directly from a drawing von Guérard made near Adelaide in 1855 of a ‘Native Kind’ (child) named ‘Carolin’ (Sketchbook XXIV, South Australia 1855, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 3, f. 84, Fig. 8). In the sketchbook he carried on the 1860 Gippsland expedition there is a particularly sensitive, undated drawing of a seated woman, ‘Nabran’, with a blanket—probably a government-issue blanket—drawn closely around her shoulders (Sketchbook XXXII, Gippsland 1860, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 11, f. 44, Fig. 9). Perhaps it was Nabran who inspired him to make such an overt reference to the displaced Gunnai people in his painting of John King’s station.

In his response to the commission to paint John King’s property von Guérard created an unsettling image, an image that reflects his awareness of and discomfort at the impact of European settlement on the Gunnai people. Like his German contemporaries in Melbourne, Ferdinand von Mueller and Georg von Neumayer, von Guérard emerged from a German intellectual tradition which revered the work and achievements of the enlightened natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt, a man whose interest in the cultures of different peoples and whose rejection of the ‘depressing assumption of superior and inferior races of men’ was well known through his publications. Von Guérard shared close and enduring friendships with James Dawson and Alfred Howitt, each of whom published pioneering anthropological studies of the Koorie people of south western and south eastern Victoria respectively. By the time von Guérard stayed as a guest on the properties of King and McMillan they had each become pillars of respectability, King as a parliamentarian and local magistrate and McMillan, among other things, as an honorary protector of Aborigines. To what extent was von Guérard aware of the massacres that had taken place in the area less than twenty years earlier? Was he aware of the involvement of his hosts (King and McMillan) and how did his patron John King respond to the haunting custodial presence of the Aboriginal people in the portrayal of ‘his’ property?

Fig. 10 Eugene von Guérard Road to the Crooked River Diggings – Mr. John King’s Station , Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, D24, f. 12

When von Guérard produced a presentation drawing of the same subject about a year later the landowner, the gardener, the Aboriginal family and even any reference to fences on the property, were erased. With the title Road to the Crooked River Diggings—Mr. John King’s Station (Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, D24, f. 12, Fig. 10), the landscape became the arena for a simpler story. Two travellers and their dog are portrayed at rest, admiring the magnificent country through which they travel; it is an image that evokes von Guérard’s own experience as a travelling artist.

On the face of it this painting—the expansive, spatially rational and topographically accurate landscape framed within the conventions of the European landscape tradition—presents us with a vision founded on the moral, intellectual and economic certainties of the European settlers. It seems to be what it purports to be. But other truths lie beneath the surface, hidden in the shadowy coulisses of the European pictorial construct. This is a secretive painting, one that requires time and close analysis and one in which von Guérard was able to stretch the parameters of the traditional property portrait to communicate his deeper response to this place and its history.

© Ruth Pullin 2012

I am grateful to Dr. Philip Jones, South Australian Museum, for his comments on an early draft of this paper.

Click on thumbnails to view larger images

- Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861, Oil on canvas laid on board, 40.7 x 83.9 cm, Private collection, England

- Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (gardener and roses)

- Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (detail)

- Fig. 4 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (detail) (parrot)

- Fig. 5 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (detail – rake and watering can)

- Fig. 6 Eugene von Guérard From Mr John King’s Station Snake’s Ridge Gippsland 19 & 20 December 1860, pencil on paper, 32.8 x 52.6 cm, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

- Fig. 7 Eugene von Guérard Bushy Park, Canoe of the Aborigines, Sketchbook XXXII, Gippsland 1860-61, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 11, f. 5

- Fig. 8 Eugene von Guérard Carolin, Sketchbook XXIV, South Australia 1855, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 3, f. 84

- Fig. 9 Eugene von Guérard Nabran, Sketchbook XXXII, Gippsland 1860-61, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 11, f. 44,

- Fig. 10 Eugene von Guérard Road to the Crooked River Diggings – Mr. John King’s Station , Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, D24, f. 12

References:

Candice Bruce ‘View of the Gippsland Alps from Bushy Park on the River Avon 1861’, in Ruth Pullin (ed.) Eugene von Guérard: Nature Revealed, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, pp. 188–89.

Humphrey Clegg ’Mr. John King’s station 1861’, in Ruth Pullin (ed.) Eugene von Guérard: Nature Revealed, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, pp. 190–91.

James Dawson, Australian Aborigines: the language and customs of several tribes of Aborigines in the western district of Victoria, Melbourne: George Robertson, 1881

Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth: how Aborigines made Australia, Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2011.

P.D. Gardner, Gippsland Massacres: the destruction of the Kurnai tribe, 1800–1860, Ensay, Victoria: Ngarak Press, 2001.

P.D. Gardner, Our Founding Murdering Father. Angus McMillan and the Kurnai Tribe of Gippsland 1839-1865, Ensay, Victoria: Ngarak Press, 1990.

A.W. Howitt, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, London: Macmillan 1904.

Alexander von Humboldt Cosmos. A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe, Vol. 1, Henry G. Bohn, London, 1849-58 (first published in Germany, 1845).

Philip Jones, Senior Curator, Australian Aboriginal Ethnology, South Australian Museum, Talk: ‘Encounters in Arcadia: von Guérard and his Aboriginal subjects’, National Gallery of Australia, 28 June 2012.

John King, day book, 1844-63, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, MSB 404, MS11396.

Nicolas Peterson, Lindy Allen and Louise Hamby The makers and making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections, Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2008

Dianne Reilly and Jennifer Carew, Sun Pictures of Victoria. The Fauchery-Daintree Collection 1858, South Yarra, Vic.: Currey O’Neil Ross on behalf of the Library Council of Victoria, 1983.

Nicholas Thomas, Possessions. Indigenous Art / Colonial Culture, London: Thames and Hudson, 1999.

Don Watson, Caledonia Australis. Scottish Highlanders on the frontier of Australia, Sydney: Random House, 1984 (1997).

Images

Fig. 1 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861, Oil on canvas laid on board, 40.7 x 83.9 cm, Private collection, England

Fig. 2 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (gardener and roses)

Fig. 3 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (Aboriginal group)

Fig. 4 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (detail) (parrot)

Fig. 5 Eugene von Guérard Mr John King’s station 1861 (detail – rake and watering can)

Fig. 6 Eugene von Guérard From Mr John King’s Station Snake’s Ridge Gippsland 19 & 20 December 2020, pencil on paper, 32.8 x 52.6 cm, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Fig. 8 Eugene von Guérard Carolin, Sketchbook XXIV, South Australia 1855, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 3, f. 84

Fig. 9 Eugene von Guérard Nabran, Sketchbook XXXII, Gippsland 1860-61, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGB16, v. 11, f. 44,

Does anybody know if this John King built 63 Caroline st South Yarra in 1855 ?

A beautiful painting, which uniquely places Aboriginal people as the primary focus. If only large scale prints were available for purchase. Not just this one, but for all Von Guerard’s paintings.

(How about it, National Gallery of Victoria?)