Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism and Baccio Bandinelli, Sculptor and Master (1493-1560)

Reviewed by Esther Theiler

Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello have provided not only welcome respite from the heat in Florence this summer but also rewarding opportunities for appraising the threads of influence of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo as they metamorphosed into the style most often characterised as mannerist. The curators at the Palazzo Strozzi have made a considered decision to call this style the “modern manner” rather than mannerism, in accordance, they believe, with sixteenth century usage (even though the English language version of the exhibition still uses ‘mannerism’). Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino: Diverging Paths of Mannerism is the first exhibition since Pontormo and Early Florentine Mannerism (a 1956 exhibition also held at Palazzo Strozzi) to bring together a substantial canon of work by these masters and it provides a chance to view the evolution of their careers. Most of the work here displayed comes from Florence, including fragile detached frescos and drawings, and it makes sense to view it here, in its city of origin. The exhibition is beautifully hung in sensitively lit rooms painted scarlet with charcoal trims that offer a sumptuous but complementary background to the richly coloured paintings. Most visitors I spoke to commented on the beauty of the setting and also on the intelligence of the structure of the exhibition and the value of the addition of rooms devoted to portraits, drawings and prints. I want to emphasise that I am not a specialist of the sixteenth century. This exhibition was a revelation to me and this ‘review’ stems more from a wish to share its marvels than to offer a critical evaluation.

On the left is Pontormo, Visitation, detached fresco, 408 x 338 cm, Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, and on the right, Rosso Fiorentino, Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1513, detached fresco, 390 x 381 cm., Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (Rosso di Fiorentino) and Jacopo Carruci (Pontormo) were born only months apart in 1494 and, aged 17, both spent a period of time in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto. According to Vasari, Pontormo had already spent time in Leonardo da Vinci’s workshop. Rosso, in turn, was heavily influenced by Michelangelo in his youth. The first room in the exhibition displays early commissions for the Chiostrino dei Voti of the Basilica of Santissima Annunziata – Pontormo’s Visitation of 1514-1516 and Rosso Fiorentino’s Assunzione of c1513. The Album of the exhibition notes the debt to Raphael of both these compositions, lending strength to the possibility that they had been in Rome with Andrea del Sarto in 1511. But it is also apparent that from the beginning, each artist had a unique and personal vision. Certainly Rosso’s penchant for putti with grotesque, goblin-like faces is apparent as is the facial structure of Pontormo’s female figures. The woman staring at the viewer in the left-hand foreground appears in equivalent figures in his 1528-29 Visitazione in Carmignano.

Room 2 features works by Rosso and Pontormo produced while engaged by del Sarto, such as Pontormo’s Joseph sold to Potiphar with its swirling kaleidoscope of gold, rose and sky blue and Rosso’s Madonna and Child with the Young St John the Baptist in which the colour signals the heightened world of affetti. In Room 3, poetically titled “Le divergenti vie: arie disperate e dolcezza di colorito” or, as is given in the English translation “Diverging Paths: Desperate Airs and Soft Colourings”, the thesis of the exhibition is laid before us visually. Here Andrea del Sarto’s statuesque Madonna and Child between St. Francis and St. John the Evangelist (Madonna of the Harpies) is flanked by Pontormo’s Sacred Conversation (Pucci Altarpiece) and Rosso’s Madonna and Child with Four Saints (Spedalingo Altarpiece). This juxtaposition serves to demonstrate the “diverging paths” that each artist took, despite their youth and employment in the same workshop. Rosso here displays the strange, transcendent and slightly grotesque vision that would be given free rein in his later paintings and prints. His Spedalingo Altarpiece,commissioned for Santa Maria Nuova, was rejected by the superintendent Leonardo Buonefede. Vasari relates that to Buonafede ‘all the saints appeared to him like devils’ and he ‘fled the house’. Pontormo’s Sacred Conversation with its triangular composition, cheerful putti and harmonious tonality was perhaps more readily pleasing.

On the left is Rosso Fiorentino, Madonna and Child with Four Saints (Spedalingo Altarpiece), 1518, oil on canvas, 172 x 141.5 cm., Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, and on the right Pontormo, Sacred Conversation (Pucci Altarpiece), 1518, oil on canvas, 221.5 x 189.5 cm., Church of San Michele Visdomini, Florence

Pontormo found favour with the display Medici while the red-headed republican Rosso fell under the influence of Savonarola and left the city in mid 1519 for Piombino, Volterra, where his most important work was done, and possibly Naples. Pontormo’s 1518 portrait of Cosimo the Elder now in the Uffizi is an extraordinary combination of a formal style made powerful by the telling use of details. The clarity of the laurel leaves contrasts with the sfumato modelling of his face. The clenched and realistic hands, the thin upper lip, intent eyes and long nose, ears bent slightly forward by his hat, his olive complexion and idiosyncratic chin, convey both a forceful personality and a hieratic type.

Pontormo, Portrait of Cosimo the Elder, 1518-19, oil on panel, 87 x 67 cm., Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

The portrait of Cosimo is the first in the room of portraits by Pontormo and it is instructive and wonderful to see them collected together in one space. The Portrait of a Goldsmith from The Louvre was displayed in an earlier room as a seductive promise of this genre. In this three-quarter composition the marvellous contrapuntal movement that Pontormo uses to good effect in his religious pictures conveys an immediacy, a sense of arrested gesture and conversation. The goldsmith looks up as if called by a person on his right while simultaneously pointing towards his left with fingers that hold an instrument. There is virtuosity in the painting of the fur edging of his coat and the starched collar at his throat and a vital communication in his eyes and partly opened lips.

At left, Pontormo, Portrait of a Goldsmith, 1518, oil on panel, 70 x 53 cm., Louvre, Paris, and at right Pontormo, Portrait of a Bishop (Monsignor Niccolò Ardinghelli?), c1541-2, oil on panel, 102 x 78.9 cm., National Gallery of Art, Washington.

This sequence of portraits shows an interesting development from the more stylised potrait of Cosimo to the informal and naturalistic Goldsmith and the Portrait of Two Friends of 1523-4, and through to the increasing distortion that characterised mannerist portraits. A quick survey suggests that while Pontormo painted faces and hands with growing naturalism and realistic skin tones, the bodies of his subjects became elongated, their shoulders unnaturally sloping and the faces small in proportion to their torsoes. For instance see the Portrait of a Bishop of c. 1541-2 (above). The best way I can put it is that the below the veil of artifice, or despite a stylistic modality, the depictions are realistic and natural, if that is not too great a contradiction. Or, as Elizabeth Cropper points out in her Pontormo: Portrait of a Halberdier, it would have been unconscionable for Pontormo to produce a strictly naturalistic portrait – in an age of self-fashioning the production of an idiosyncratic style was an essential and expected element, the calling card of the artist.

While Pontormo’s room of portraits is titled “Lifelike and Natural”, Rosso’s, in Room 5, is called “Harshness of Features”, which seems a little, well, harsh. Stern might be a better term. Vasari said that many families in Florence (those opposed to the Medici) had portraits from Rosso in their houses, but none of those on display are identified. Despite the increasingly visionary nature of his other painting, his portraits are sombre and static, but also dignified and expressive. This is not quite as contradictory as it sounds. The first portrait one encounters in this room is Fra Bartolomeo’s Portrait of Girolamo Savonarola. His beak-like face appears to regard with approval the solemn demeanour, and black and white clothing of the subjects, many of whom hold letters or books that attest to their seriousness. (There is an exception to this in the Portrait of a Young Man from the Capodimonte in Naples that was for a long time thought to be by Parmigianino). Rosso Fiorentino’s Ginori Altarpiece, The Marriage of the Virgin in Room 6, painted after Rosso returned to Florence in 1522, demonstrates this demarcation between the world of reality and that of the spirit that was a legacy of Savonarola. In this newly-cleaned work painted for Carlo Ginori, a follower of Savonarola, in 1523, the only sombre figure is that of a Dominican, possible Saint Vincent Ferrier. Savonarola could not be portrayed in Florence at this time and it is thought that the Dominican stands in for him. This man represents the life that must be lived seriously and with restraint, as seen also in the portraits. The rest of the composition is not of this world, it is a vision of another time and place, a transcendent realm, the afterworld described by Savonarola as the reward for the virtuous. It is a crowded composition demonstrating what Vasari described as Rosso’s horror of space. The gelati colours, the rose pink, teal, caramel, tangerine and pistachio, represent the transcendental, the spiritual world in which these events take place. (Of course in Italy these worlds can co-exist – after all we see these colours everyday in the clothes of Italians walking the streets.)

Rosso Fiorentino, The Marriage of the Virgin, (Ginori Altarpiece), 1523, oil on panel, 325 x 247 cm., Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence. (My apologies – this is the uncleaned version)

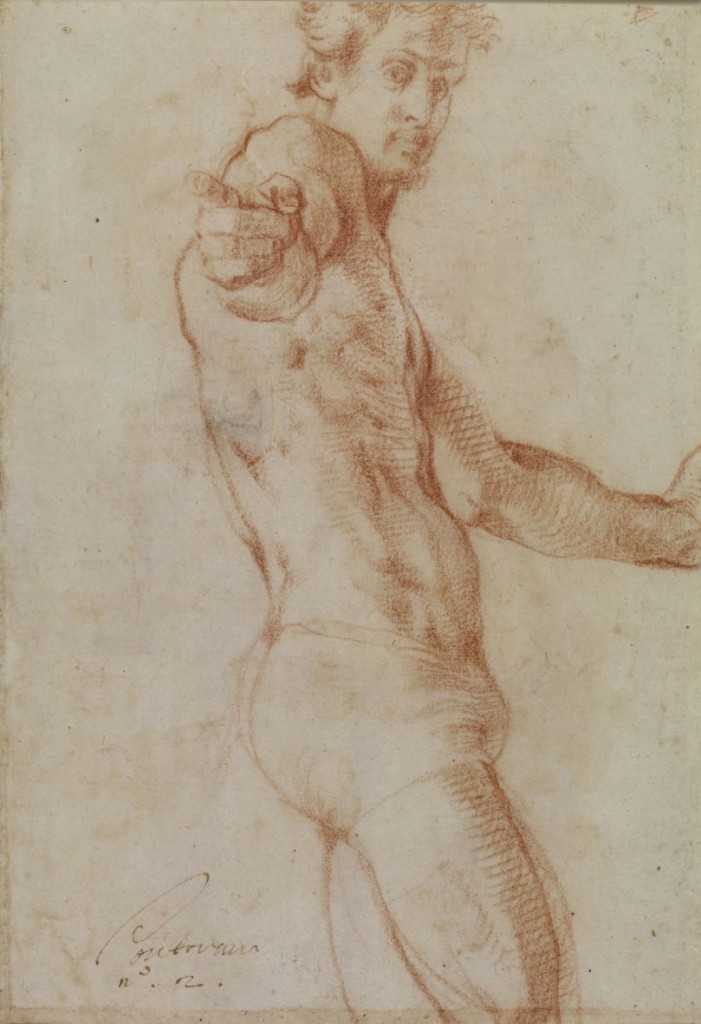

Vasari said that Rosso was ‘extremely studious’ in his approach to painting and had dead bodies exhumed in the Vescovado from which he made anatomical models and that he drew frequently. One of the highlights of this exhibition is the opportunity to view the drawings of both artists. A room apiece is devoted to the sketches and designs of each artist and each room feels like a concentration of the fine and exceptional draughtsmanship that underlies their achievements. Pontormo’s Study of a Nude from the British Museum (possibly a self-portrait) is startling for the originality of its composition and its immediacy. The smudges on the paper, the intimate hollow in the elbows, the corrected leg and buttocks, bring us close to the moment of its inception. The viewer finds him or herself in the confusing position of looking into the eyes of Pontormo, close to his pointing index finger, but knowing that he sees, instead, either himself or another.

Pontormo, Study of a Nude (Self-portrait), red chalk, 284 x 202 cm., British Museum, London

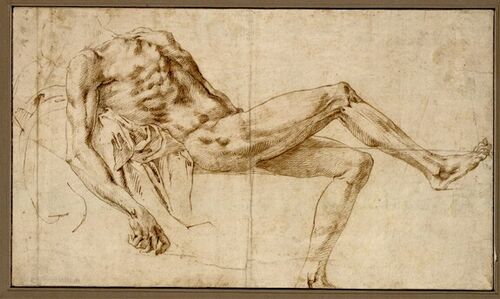

Rosso left fewer drawings behind, but eleven are shown at Palazzo Strozzi, dating from various periods of his life. Michelangelo was an early and strong influence, but Rosso developed a more intense, private and conceptual approach early on. His Holy Family with the Young St John the Baptist mentioned earlier, prefigures the hallucinatory work of Odilon Redon and other French symbolists. The room devoted to engravings after his designs offers a vivid impression of his macabre vision and his delight in a medium that allowed his to share his vision with a wider audience.

Rosso Fiorentino, Study of a Nude for Christ in the “Deposition” at Sansepolcro, 1527, brown ink on paper, Albertina Museum, Vienna

The curators refer to the influence of Dürer on Pontormo, an aesthetic choice that put him out of favour when Vasari later wrote his Life. However he continued to enjoy major commissions, such as the Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicita and the choir of the Basilica of San Lorenzo. Rosso moved to Rome in 1525 and was subsequently captured during the Sack of Rome in 1527. He escaped to Perugia and Arezzo but moved to France and the court of Francis I in 1530 and employment in the Château of Fontainebleau (his cartoons for tapestries and some of the tapestries are displayed here) where he died young in 1540.

On the left, Rosso Fiorentino, Holy Family with the Young St. John the Baptist, c. 1521-2, oil on panel, 63.5 x 42.5 cm., The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, http://art.thewalters.org/detail/29457/the-holy-family-with-the-infant-saint-john-the-baptist/ , on the right, Gian Giacomo Caraglio after Rosso Fiorentino, Fury, 1524, engraving, 250 x 184 mm., The British Museum, London.

A short walk away from Palazzo Strozzi in the Bargello Museum, a small exhibition was, until a few days ago, devoted to Baccio Bandinelli, 1493-1560, one of the most important sculptors of the sixteenth century and a close contemporary of Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Curated by Detlef Heikamp and Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi and displayed in stone walled rooms on the ground floor, the earthy setting was appropriate for Bandinelli’s powerful sculptures in marble, bronze and terracotta. According to Vasari, his one-time student and later critic, he was encouraged by Leonardo da Vinci and envious of Michelangelo. I won’t attempt here to make an appraisal of the marvellous collection of sculptures, including some recent attributions, that fill the rooms, but rather note the points of connection with the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition. These are the common influences of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Andrea del Sarto, among others, the opportunity to view a fine selection of drawings by Bandinelli and the concentration of a collection of portraits – in this case including many self-portraits and the early portrait of Bandinelli, here labelled ‘after’ Andrea del Sarto.

On the left, Florentine painter after Andrea del Sarto, Portrait of the Young Baccio Bandinelli, 1st half of the 16th century, oil on canvas, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, on the right, Baccio Bandinelli, Self-Portrait, c1545, oil on wood, 142.5 x 113.5 cm., Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

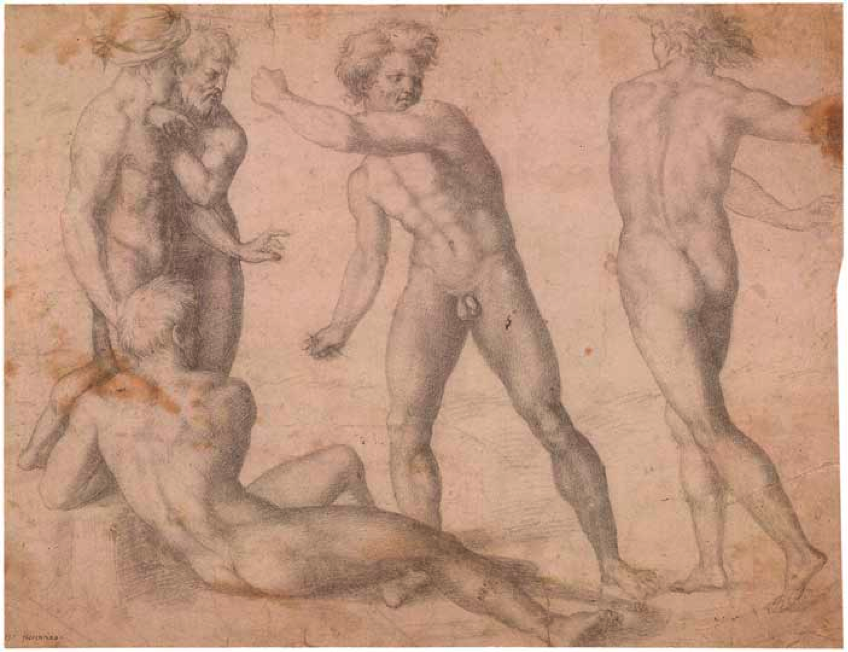

Also included were a bas-relief self-portrait and a terracotta self-portrait from The Ashmolean. Of the drawings, many were from the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, including his sketch of Cosimo I and numerous studies for other works.

Baccio Bandinelli, Study for Nudes in Combat, c1512, black pencil, British Museum, London.

The strength of his draughtsmanship, like that of Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo, prompts a deep admiration for the versatility and breadth of his artistry. Taken together these two exhibitions provided a unique opportunity and a rich entry point for the appreciation of a trio of artists sometimes overlooked and undervalued but important for an understanding of late Renaissance art history. To see them in Florence, where much of their context is embedded, is to gain a whisper, a scent, of lives lived in this vivid and treacherous city.

© Esther Theiler 2014.