Rome: Piranesi’s Vision

Katrina Grant

State Library of Victoria, 22nd February until 22nd June 2014. Free exhibition.

‘When I first saw the remains of the ancient buildings of Rome lying as they do in cultivated fields or in gardens and wasting away under the ravages of time, or being destroyed by greedy owners who sell them as materials for modern buildings, I determined to preserve them for ever by means of my engravings’ – Giovanni Battista Piranesi

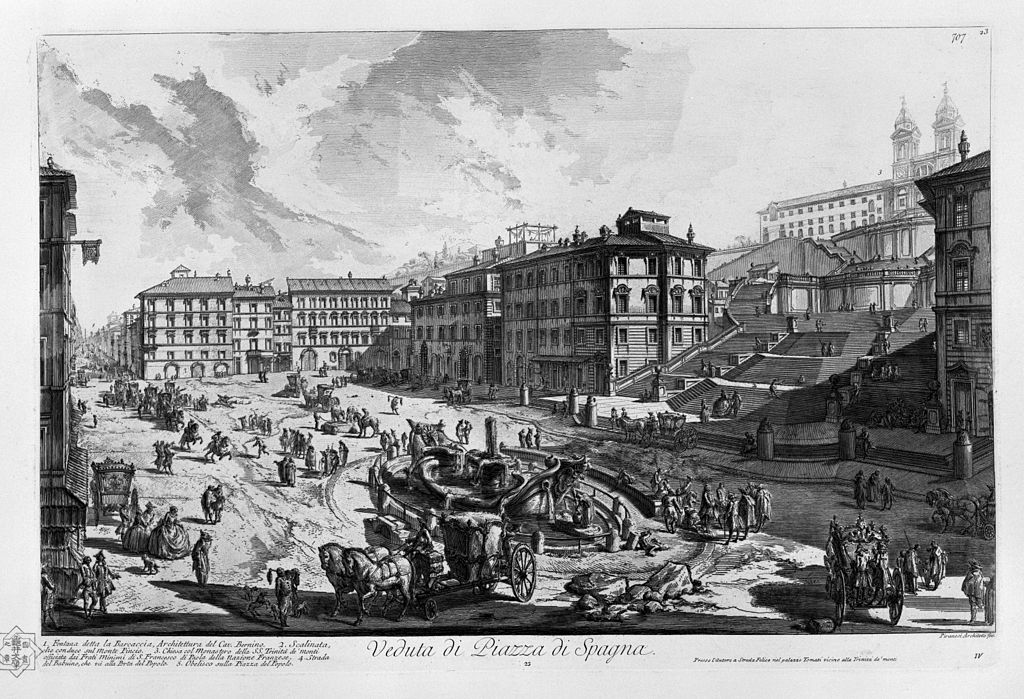

Piranesi wrote this in his preface to the Antichità romane and it is just one of his many statements that declare his dedication to Rome. His views of Rome stand as a record of the past glories of Ancient Rome, each engraving carefully labelled so that we can identify the fragments of ruined monuments. They also record aspects of the Early Modern city of Rome that are also now, in many ways, lost. We see Rome on the cusp between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries-when Rome that was reshaped by ambitious papal building projects and urban transformations (as seen in Piranesi’s views of St Peter’s Square, the Piazza del Popolo and the Piazza Navona)-and Rome of the modern era, which Piranesi highlights in engravings of recent building projects such as the elegant Spanish Steps (completed in 1725) [Fig. 1] and the Villa Albani (home to Cardinal Alessandro Albani a major patron of art and architecture and at the centre of the key intellectual circle of eighteenth-century Rome).

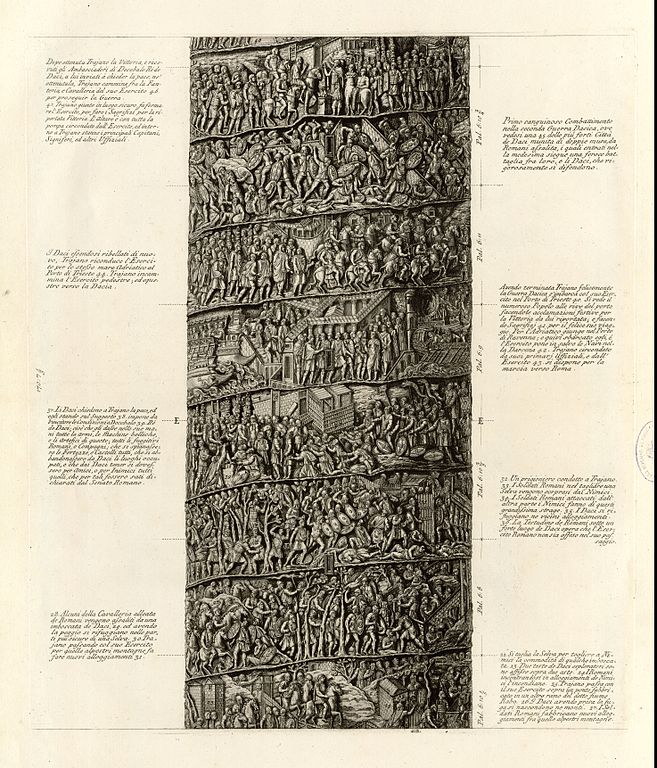

The first thing you see as you enter the exhibition is Piranesi’s View of the Principal Prospect of the Column of Trajan unfolded in full. This engraving is an excellent introduction to the exhibition: it shows Piranesi’s ambitious use of printmaking on a grand scale (it is nearly three-metres long); it shows his skill as an engraver (the engraving is densely detailed yet still conveys a sense of the three-dimensionality of the column and its low-relief sculpture); and it shows Piranesi as not just a vedutista, but as a sort of proto-archaeologist who carried out careful and empirical study of Roman architecture, and of ancient Rome in particular. The engraving of Trajan’s column is carefully labelled and allows the viewer to carry out a close examination of the carved reliefs of Trajan’s column, something that is impossible to do standing at the foot of the thirty-metre high column.

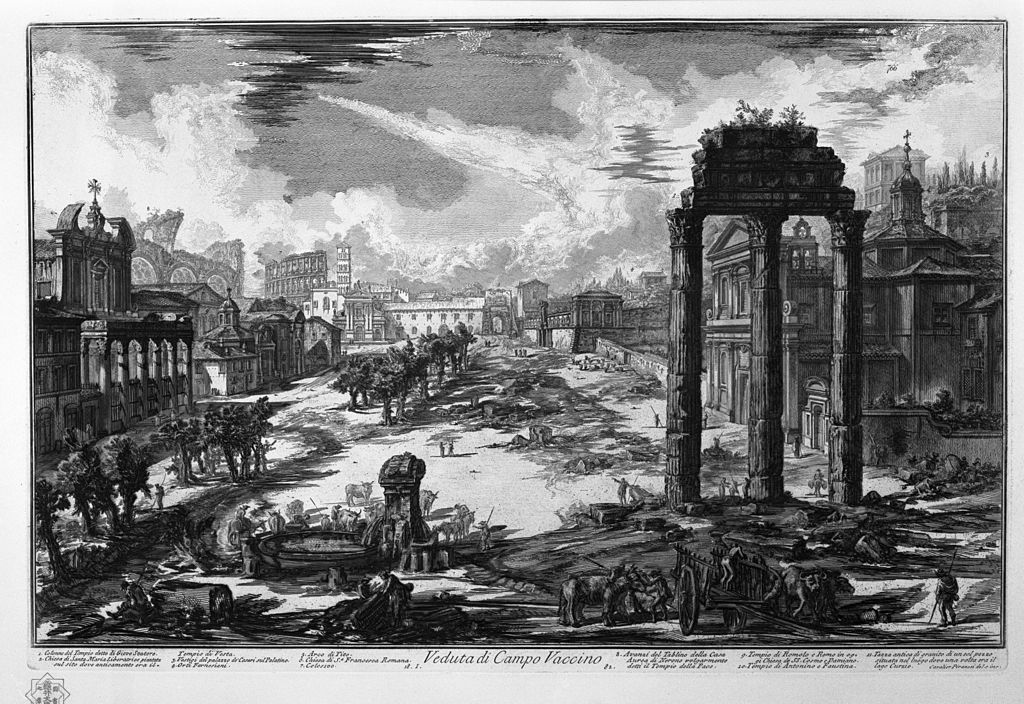

From here the eye is drawn to the views of the Roman Forum that are displayed in the centre of the gallery. Piranesi’s engravings are displayed alongside Bernardo Bellotto’s painted view of the forum (from the NGV collection). Piranesi’s Veduta di Camp Vaccino [Fig. 3] is taken from the mid point of the forum and shows the Campo Vaccino covered in people going about their daily life, mostly taking very little notice of the antique monuments; water is collected at a trough since removed to the Piazza Quirinale; a herd of goats graze near a wall and a cart is unloaded near the three columns of the temple of Castor and Pollux. In his book on the Roman Forum the architectural historian David Watkin has pointed out that the ‘period when it was in use by the ancient Romans as a working Forum was far shorter than the millennium and a half that has passed since the fall the their Empire’. This is what Piranesi’s engraving and Bellotto’s painted view both show. The Roman Forum as a blend of old and new, the remains of ancient monuments are interspersed with remains of Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Rome. We can see the still relatively new seventeenth-century façade of the thirteenth-century church of Santa Maria Liberatrice is glimpsed through the three columns of the Temple of Castor and Pollux. Facing it is the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, which is blended with the seventeenth-century church of San Lorenzo in Miranda.

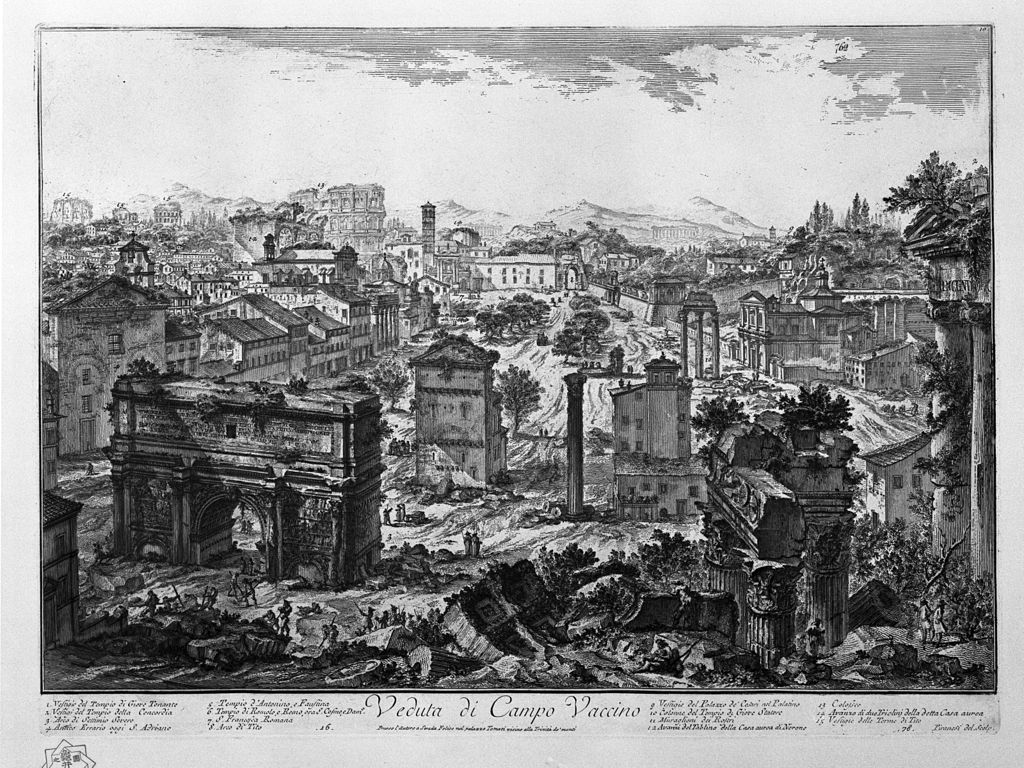

Another of Piranesi’s views of the forum [Fig. 4] is from the viewpoint of a window in the Palazzo Senatorio and shows more of the half-buried ruins of the forum. Figures with spades are digging around the Arch of Septimius Severus, anticipating its excavation in the nineteenth century. Excavations that, in the case of the forum at least, have swept away much of the mix of Roman, Early Christian, Renaissance and Early Modern city that we can see in Piranesi’s vedute. Although Piranesi’s prime concern was the recording of the ancient buildings of Rome, his engravings also show us parts of Early Modern Rome that are now lost, such as these rustic fields that used to surround the ruins in the Roman forum or the crowded river ports of the Tiber as shown in the Veduta del Porto di Ripa Grande [Fig. 5] before they were demolished in the nineteenth century so that the Tiber embankments could be built.

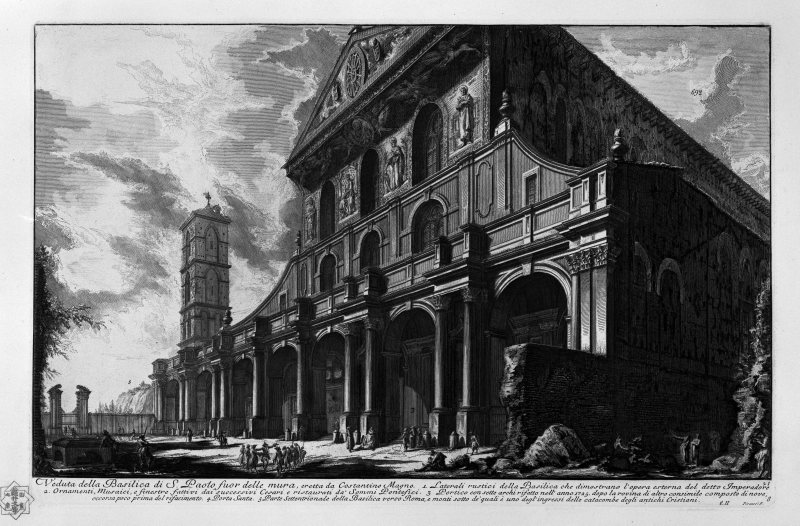

Piranesi’s engravings were in high demand by Grand Tourists and other visitors to Rome, such as artists and architects. His views came to characterise the ‘idea’ of Rome in the mind of the eighteenth-century traveller. His engravings also show that attitudes towards the buildings and monuments of Rome were changing rapidly. If you look closely at the keys on his engravings you can see that they are more than just descriptions. In many cases he identifies only the antique remains (as in the prints of the forum where none of the churches are identified), and in others he directs the viewer to points of historical interest that are not actually visible in the engraving. In the vedute of the Basilica of San Paolo fuori le mure [Fig. 6] Piranesi has labelled the non-descript hill in the background to let the viewer know that under the hill is one of the entrances to the early Christian catacombs. While two figures on the right-hand side seem to be admiring not the church façade but the ancient stone wall.

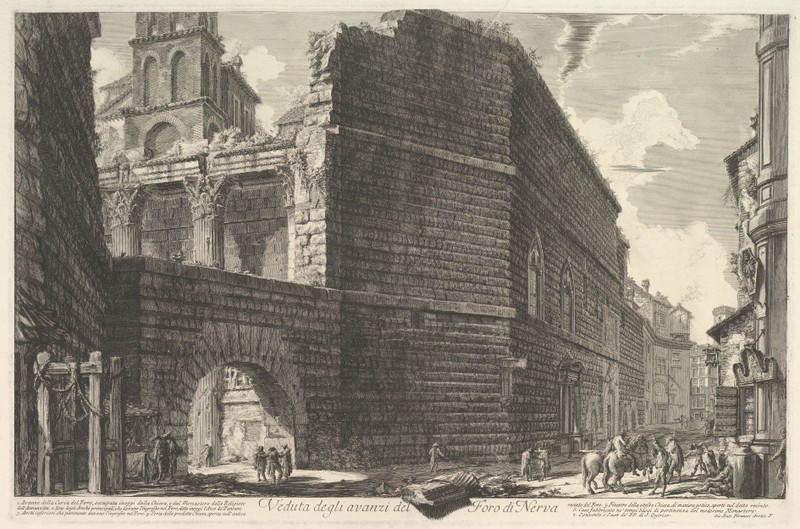

An engraving by Marco Alvise Pitteri after Francesco Lorenzi of a portrait of Scipione Maffei is included in the exhibition. Maffei was a scholar of antique Rome and one of a growing number of intellectuals who advocated close study of the remains of antiquity (as opposed to only studying it via literary sources). The work of Maffei and others had a significant impact on Piranesi’s approach and the selection of engravings in this exhibition clearly demonstrates that Piranesi conceived the vedute as a contribution to historical and archaeological study. He is not simply recording views of Rome, he is actively studying and documenting the past. This attitude explains the rationale behind views such as the Vedute deli avanzi di Fora di Nerva [Fig. 7] (actually the Forum of Augustus) where the focus of the print is on the enormous masonry of the ancient wall – now incorporated into a church and monastery. Piranesi hasn’t chosen the most picturesque point-of-view, but the one that bests allows him to show the historical importance of the monument.

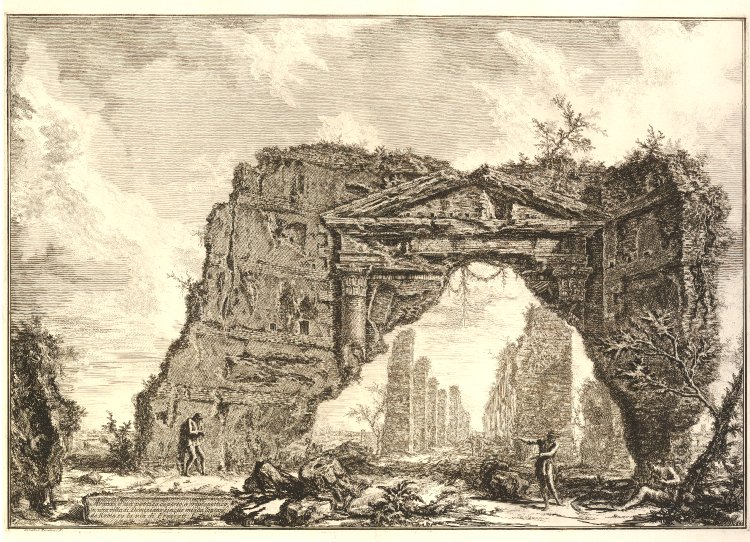

In other engravings Piranesi has abandoned any attempt to present a view of Rome as it was in the eighteenth century. Instead he combines his careful empirical observations of actual monuments and sites in Rome with imaginative recreation or invention. His Via Appia Antica [Fig. 8]is like a mash-up of ancient Rome. The tombs of the ancient Romans found along the Via Appia Antica are transformed from ruined remnants into elaborate architectural assemblages. The tombs have been embellished and are now piled one upon the other. This fusion of archaeology and imaginative speculation is also present in Piranesi’s Ichnographiam Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis, in which he has used the fragments of the antique Severan marble plan as a jumping off point to re-imagine ancient Rome. In some places greatly extending known buildings, and in others creating new ones.

Along with his dramatic use of light and shade (note how often the foreground buildings and fragments are in dense shadow as in his view of the Pantheon), Piranesi uses exaggerated perspective in an effort to convey the emotional effect of standing in the shadow of Rome’s buildings. Piranesi worked in the theatre and a couple of views appear to directly reference set design. This is most striking in one of his views of what he believed to be the Villa of Domitian. In Avanzi d’un portico coperto [Fig. 9], Piranesi’s shows a ruined wall with the remains of the columns and pediment that formed the entrance to the villa. The lower parts of the wall and columns have fallen away to reveal a view of a ruined portico behind. The doorway seems to deliberately reference the type of proscenium arch based on classical architecture common in eighteenth-century theatres, and the view of the ruined portico mimics stage flats.

Others demonstrate his knowledge of the new technique ‘scena per angolo’ ‘scenes at an angle’ developed by the Bibiena family. In the view of San Paolo fuori le mure [above Fig. 6] the view of the church façade is set at an extreme angle. The top of the church’s façade is pushed out of the picture, with the effect that it seems to tower over us, even in two-dimensional engraving. Rarely do we experience the architecture of Rome (or many other cities) from the easy, middle-distant, slightly raised viewpoint that is often favoured in views of Rome (such as those by Vasi). Instead we tend to suddenly emerge from an enclosed street into an open space like the Piazza Navona, or we stand with our backs pressed against the stone wall of a building opposite and crane our necks to take in a facade on a narrow street.

The inclusion of other paintings, engravings and printed books by other artists, such as Piranesi’s collaborator Robert Adam and fellow engraver Giuseppe Vasi, is a strength of the exhibition. They reveal not only the impact of Piranesi’s particular style on subsequent artists but also demonstrate how widespread the desire for images of the antique world was. They also provide further context for Piranesi and his art and draw the viewer more deeply into the milieu of eighteenth-century Rome. The NGV has lent three paintings – a portrait by Pompeo Batoni, who, like Piranesi produced much of his work for visitors to Rome (though in this case the portrait is of a Roman aristocrat, Duke Gaetano Sforza-Cesarini). There is also Bellotto’s view of the forum [Fig. 10] and an architectural capriccio by Panini. The fact that a relatively small exhibition can draw on other local collections to bring together key eighteenth-century artists such as Piranesi, Panini, Batoni and Bellotto is a reminder that our Melbourne galleries and libraries have extremely fine collections of eighteenth-century art.

Along one wall are several vedute by Giuseppe Vasi (1710-1782) an almost exact contemporary of Piranesi. Like Piranesi, Vasi produced numerous views of Rome, recording the ancient and modern city. Vasi’s Porta di Ripetta (1754) [Fig. 11] shows Rome as an elegant and relatively modern city. His focus is on the elegant curved staircase of the Porta di Ripetta, still a relatively new addition to Rome (completed 1703). His composition is also carefully balanced into three horizontal bands: river; buildings; and sky. The lopsided masts and sails of the small boats add short vertical accents. We can easily contrast Vasi’s approach with Piranesi’s Veduta del Porto di Ripa Grande [above Fig. 5]. Here Piranesi has exaggerated the long façade of the palazzo and pushed the masts of the boats, the messy vegetation and fragments of antique buildings on the opposite bank right up against the picture plane. The river looks crowded and disorganised. The viewpoint is lower and Piranesi’s characteristic use of dark shadowing in the foreground contrasted with a lighter background adds the ‘sense of drama’ so often invoked in descriptions of his engravings.

The works are displayed in the compact Keith Murdoch Gallery at the State Library of Victoria. This works well–while there is some loose grouping of works (Grand Tourists, Early Piranesi and so on)–the engravings, paintings and books included in the exhibition are all closely connected and it is good to be able to move quickly between parts of the exhibition to make comparisons as they occur to you. It also means that the engravings don’t get lost in a vast space, the compact gallery encourages you to get up close to the prints and this is a good thing as the dense detail rewards close looking.

The exhibition is complemented by two other exhibitions currently on in Melbourne, one at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, The Piranesi Effect, which includes works by contemporary Australian artists that respond to Piranesi. And another at the Italian institute of Culture of contemporary Italian photographs of Rome.

© Katrina Grant 2014