Australian Impressionists in France

Caroline Jordan

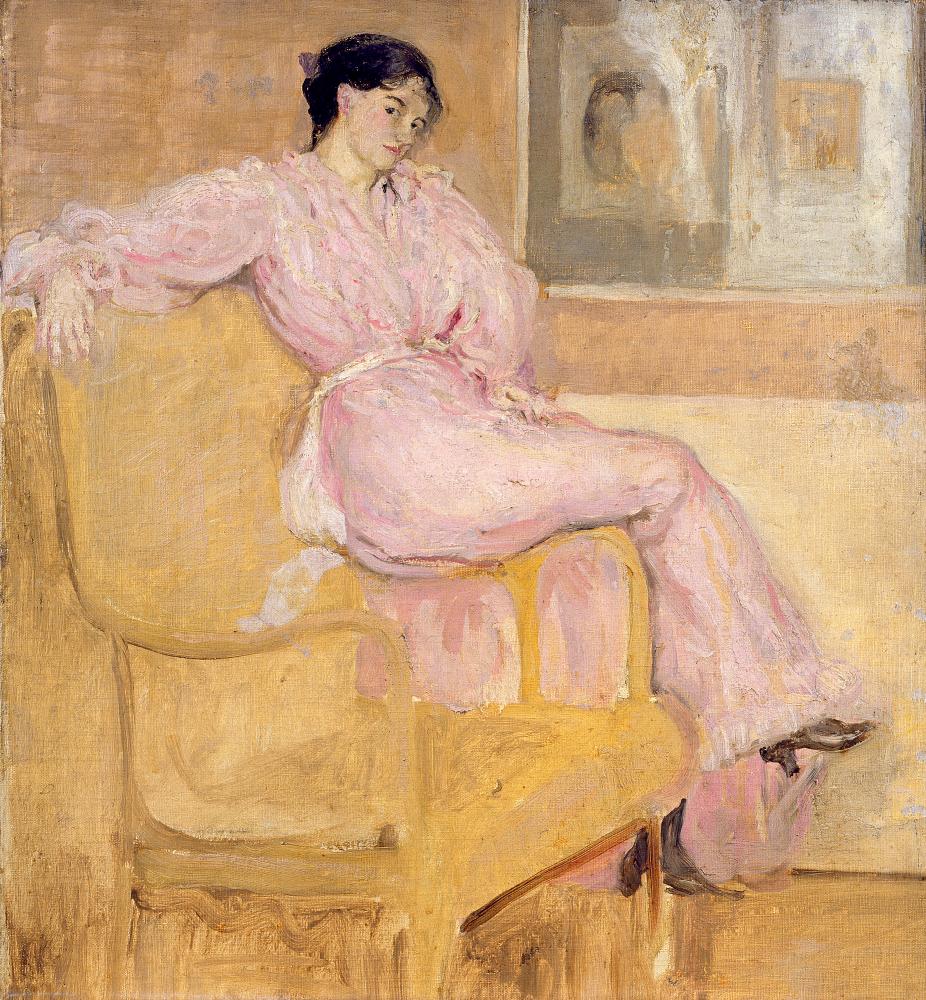

Charles Conder England 1868–1909, lived in Australia 1884–90, Europe 1890–1905 Mrs Conder in pink c.1901 oil on canvas 48.0 x 44.3 cm New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, Leicester Purchased by the Friends of the Museum, 1956 (L.F43.1956) © Leicester Arts & Museums/The Bridgeman Art Library

The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) has offered a number of Impressionist blockbusters over 2012-13: Monet’s Garden, Radiance: the Neo-Impressionists and now Australian Impressionists in France. Given its present ubiquity in our state gallery, it is well to remember that when Impressionism debuted in France in the 1870s and 1880s it was considered to be beyond the pale of official patronage. Impressionism offended by rejecting the mythological, classical or historical subject matter of academic painting, replacing it with such unimportant things as dance halls, picnics, cabbage patches, haystacks, stretches of beach and random scenes of the street. Spurning the studio, the Impressionists ventured outdoors to paint direct from the motif, daubing slashes and spots of pure, bright colour onto white-primed or bare canvases. Impressionist compositions were similarly innovative, drawing on the novel influences of Japanese art and photography; they might be elongated, off-centre or conceived from extreme angles, with figures popping up in odd places, or half cut off by the frame.

Impressionism’s lack of ‘finish’, high-key colour and loving attention to banal or incidental subject matter once baffled and irritated audiences and critics. To the contemporary sensibility, however, Impressionism appeals as the most accessible of all nineteenth and twentieth century modern art movements. Australian Impressionists in France shows why. At first glance, it offers the visitor a pleasant, nostalgic immersion in foreign travel. White walls picked out with bright green accents evoke a Mediterranean holiday, reinforced by the many scenes of people relaxing and milling about on beaches, in cafes and bars, and in gardens, flower markets and exotic bazaars. Studies of the figure are overwhelmingly of lovely sunlit young women in sensuous attitudes of repose. Landscapes commemorate the fleeting splendours of summer at the seaside or of spring orchards in blossom. Apart from a few city street scenes and a few dour life studies and studio portraits to suggest the labour of the artist, there is a remarkable absence of any signs of industrialisation in these landscapes, or of the toll of labour on the urban or rural working classes. French Impressionism did not shy away from the latter subjects – think of Monet’s pictures of steam trains or Degas’s paintings of tired ballerinas and laundresses – but such themes evidently did not inspire imitation by their Australian followers in France.

Australian Impressionists in France (or ‘AIF’) has been conceived as a companion exhibition to the 2007 blockbuster, Australian Impressionism, countering the latter’s organising nationalist theme with internationalism. The exhibition amply demonstrates how Australians in Paris mingled and exchanged ideas with their English-speaking counterparts from New Zealand, Canada, the USA, as well as with French and foreign students from many other countries. Often, they met at private art schools like the Académie Julian or Colarossi’s which allowed entry to those who did not speak French. These private schools were considerably less stuffy than those of the official academies, even offering drawing from the nude for lady artists. Outside the schools, the artists shared cheap rooms and studio-complexes in Montmartre or Montparnasse, where bohemian identities could be tried out with more impunity than in Adelaide or Auckland. Foreign artist networks also spread well beyond the capital into the French countryside because, then as now, Paris shut up shop over the summer months. The artists escaped to picturesque Brittany, or to artists’ colonies such as those at Étaples, on the Picardy coast, or Giverny, the small village outside Paris made famous as the location of Monet’s house and garden.

AIF is a much looser, more eclectic and sprawling show than the tightly-focused Australian Impressionism. The latter concentrated on only a handful of canonical artists: Arthur Streeton, Charles Conder, Tom Roberts, Fred McCubbin and (in a mildly controversial inclusion) Jane Sutherland, whereas AIF explores the lure of Paris for a couple of generations of provincial yet ambitious artists. A few ‘stars’ of the show are represented by substantial suites of paintings; the most dominant being John Peter Russell, followed by Conder (who departed Australia in 1890 at the age of 21 to become a permanent expatriate), Ethel Carrick and her husband E. Phillips Fox, Ambrose Patterson, Tudor St George Tucker and Hilda Rix Nicholas. However, many artists are represented by only one or two works. These include Will Ashton, Rubert Bunny, Bessie Davidson, Florence Fuller, Bessie Gibson, Hans Heysen, John Longstaff, McCubbin, Margaret Preston, Iso Rae, Hugh Ramsay and Sutherland. Also included are examples of work by the New Zealander Frances Hodgkins, the Englishman William Rothenstein, the American Frederick Friesecke, and the great French artists Pierre Bonnard, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edouard Vuillard.

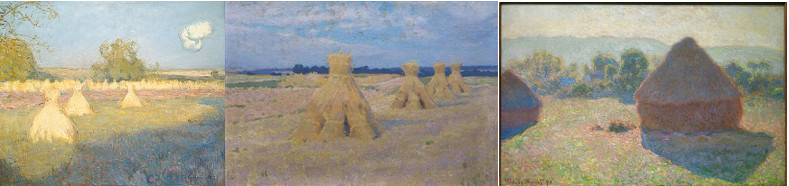

L-R Charles Conder, Hayfield France, 1894, AGSA; E. Phillips Fox,Wheat stacks, Giverny, 1892, private collection; and Claude Monet, Haystacks, 1890, NGA

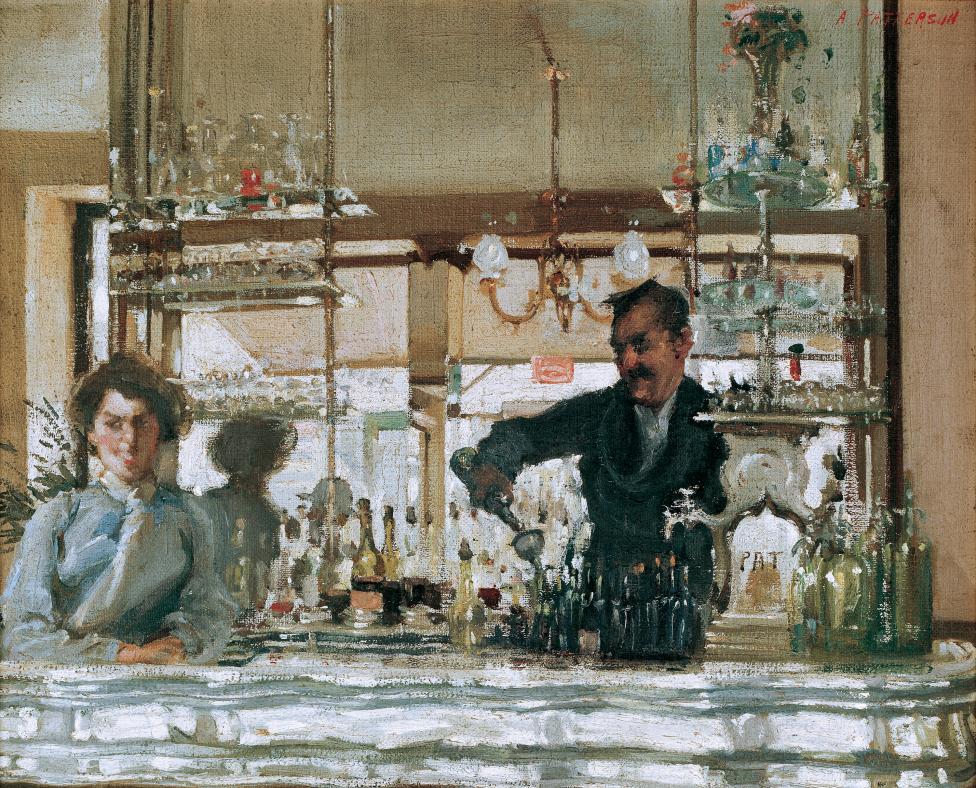

The representation of this legion of Australian artists and of foreign artists serves to illustrate networks of friendship or tutelage, and/or of direct artistic influence. It is gratifying to see the NGV’s familiar and substantial paintings by Monet, Bonnard, et al, recontextualised here as reference points for the Australians, especially since the split of the NGV into its Australian and international galleries now makes such comparisons more difficult. Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre, morning, cloudy weather (NGV, 1897), an elevated view of the anonymous activity of the street, for example, finds its echoes in otherwise unremarkable and more conventional paintings by Heysen, Ashton and Patterson, dating from 1901 to 1909. Conder’s Hayfield, France (1894) and E. Phillips Fox’s Wheat Stacks, Giverny (1892) both qualify as direct homages to the master, Monet, and I regretted they were not joined by his Haystacks, Midday (1890,National Gallery of Australia). Comparisons such as these, it must be said, are invariably somewhat to the detriment of the Australians, but demonstrating originality is not really the point of this exhibition. It consists of lots of things that remind one of other things. It is impossible to look at Ambrose Patterson’s jolly oil sketch of servers behind a mirrored bar in Le Bar, St Jacques, Paris (c.1904) without thinking of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergere (1882), for example, even though they are quite different stylistically.

Ambrose Patterson, "Le bar, St Jacques, Paris", c.1904, oil on canvas, 48.2 x 59.7cm, Art Gallery of South Australia.

While Patterson painted this picture after Manet’s death, others managed to meet their heroes. The exhibition places much emphasis on John Peter Russell’s personal acquaintances with some of the masters of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Russell was a wealthy expatriate whose private income allowed him the luxury of combining a progressive artistic calling with a comfortable bourgeois family life. He was one of the first Australians to study in Paris, in 1884 at the Atelier Cormon, where his fellow students included Toulouse Lautrec and Vincent Van Gogh. The latter was warmly supportive of Russell’s painting. Indeed, Russell’s paintings of the late 1880s such as Madame Sisley on the banks of the Loing at Moret (1887) and Peonies and head of a woman (1887) are among his most interesting and experimental, particularly in their flat, Japanese-inspired compositions. In 1888 Russell and his Italian wife moved to Belle-Ile, fourteen kilometres off the coast of Brittany, where Russell introduced himself to Monet, who was painting outdoors at the time. Monet found Russell charming and hospitable and Russell found Monet’s manner of painting the rugged Breton cliffs and choppy seas inspiring and worthy of imitation. Russell also knew the sculptor Rodin and the younger painter Matisse. Russell eventually returned to Australia, continuing to paint, but not to exhibit. It was not until the 1970s that he was rediscovered.

The relationship of Australian artists with less well-known artists is also notably explored in this exhibition. Frederick Friesecke, for example, was the leader of a small group of American artists centred on Giverny. E. Philips Fox and his wife knew Friesecke well, and the inclusion of his Breakfast in the Garden, (c.1911), an exquisite exercise in vivid green, offers evidence of his direct influence on Fox’s large, sun-dappled pictures of elegant blonde women in domestic garden settings. Also unexpected are some unusual watercolours, worked wet on wet, by the New Zealand expatriate artist, Frances Hodgkins. Hodgkins made a successful career as an art teacher in Paris in the early 1900s, and taught Australian students Bessie Gibson and Kathleen O’Connor.

Frederik Frieseke, Breakfast in the Garden c. 1911 Oil on canvas, 26 x 32 5/16 in. (66 x 82.1 cm) Frame: 36 x 45 5/16 in. (91.4 x 115.1 cm) Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1987.21

Many of the works in AIF are intimate in size and subject matter, yet this is a surprisingly big exhibition on a blockbuster scale. For this reviewer, this is an incompatibility that is not entirely satisfactorily resolved. The exhibition is organised chronologically, beginning with art school exercises from the mid to late 1880s and ending with the first decades of the twentieth century and the transition to modernism. The evenly-spaced and single-hung works are spread out over the eight large, high-ceilinged rooms of the Ian Potter Centre gallery. The problem with the regular rhythm imposed by the hang in these large spaces and the uninspired chronological structure is that it dissipates the impact of the mini-narratives within the show. I felt it would have been better served in a smaller space with tighter, more thematic and more varied groupings, like the impressive Sydney Moderns which recently closed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. In AIF smaller-sized works such as the series of exotic and usually vibrant Ethel Carrick Fox market pictures seem somewhat lost; strung out against the big white walls, despite their high colour. Elsewhere, the chronological hang seems ‘bitty’. For example, the distinctive and rather anomalous watercolours by Hodgkins and her followers are oddly spaced out in adjacent rooms, which doesn’t serve the works well or enable comparisons between them. There is also a lack of balance between the under-representation of an artist like Hodgkins and the over-representation of Russell, who has substantial groupings of his early, middle and late works spread out across three rooms of the show.

Perhaps a closer exploration of key locations such as Paris, Etaples, the artists’ colony favoured by the Australians, Giverny and Brittany might have pulled the works together in more satisfying and instructive configurations. Perhaps, too, the exhibition’s confinement to the period of Impressionism was too limiting. Paris remained a Mecca for Australian artists into the 1920s and 1930s. One could imagine a different Paris-based show that extended from impressionism into modernism and explored the impact of Cézanne and Cubism on Australian art. However, I doubt whether the average viewer will allow these criticisms to intrude on their enjoyment of the show. The exhibition contains many fine paintings which are not often seen, and its generous inclusiveness allows for refreshing insights into the overseas training, influences and careers of Australian artists abroad.

© Caroline Jordan 2013

The exhibition ran at the NGV Australia from 15th June – 6th October. You can still view the website here.